The Christ of Nikos Kazantzakis

Few atheists have been as Christ-haunted as Nikos Kazantzakis (1883–1957), the Greek writer perhaps best known as the author of Zorba the Greek and The Last Temptation of Christ.

Besides being the eponymous (and infamous) protagonist of the latter novel, Christ appears as a subject or driving idea of numerous personal letters, plays, and novels, standing alongside the similar self-actualizing figures of Buddha, Nietzsche, and Lenin as one of Kazantzakis’ guiding luminaries.

As is evident from this eclectic list, Kazantzakis was a complex individual with often contradictory views. Like one of his other heroes, Odysseus, he was a volatile itinerant, liable to be misunderstood by his contemporaries and by later readers. Called a Bolshevik by the right and a bourgeois mystic by the left—both accusations he partly welcomed—Kazantzakis was a political writer who aimed his political art at something beyond the purview of everyday factionalism.

The Transubstantiation of Flesh into Spirit

Kazantzakis’ towering literary output reflects a lifelong effort to articulate both spiritual and political radicalisms, for which the figure of Christ is often the embodiment. What his biographer Peter Bien calls an “eschatological politics” found expression in his art, in his participation in political activities, and in his idiosyncratic faith—which, while atheistic, never truly left a Christian orbit. Flitting between various forms of partisanship throughout his life, Kazantzakis never arrived at an exterior home for his beliefs. Instead, argues Bien, he sought a particular form of “personal salvation by political engagement,” in which the self-conscious Nietzschean individual, remade by a tragic acceptance of life, brings his worldly actions into harmony with the ever-progressing evolution of an immanent Spirit.

This was the new post-Christian religion Kazantzakis developed from the philosopher Henri Bergson, whose lectures he attended in Paris in 1908. Bergson’s concept of a vital force directing the evolution of all matter toward spiritual refinement—the “transubstantiation of flesh into spirit,” in Bien’s phrase—became the overarching obsession of Kazantzakis’ life and art. This belief, far from being a source of consolation, was rather an attempt to make sense of his chaotic struggle with the material world, most especially in the failures he experienced in politics. Crucially, the “eschatological” element of his mature worldview meant that Kazantzakis pessimistically deferred the transformative rebirth of all structures and values that he so desired until a future always just beyond reach—a consequential view which I will consider more below.

It must be emphatically stated up front that while Kazantzakis’ philosophical and political views often aimed at a radical transformation of exploitative systems in ways that overlap with positive social change (he remained committed to socialism as an ideal throughout his life), I don’t think they offer any kind of model to emulate. The suspect nature of his Bergsonian-Nietzschean system of values is readily seen in his early belligerent nationalism, his frequent praise of violent force, and his one-time attraction to Italian fascism.

Such dangerous chauvinism attested to the belief that the modern soul was caught in a “transitional age,” a time marked by decadence of the spirit that must be overcome through the assertion of new universal myths and values. Like his contemporary Thomas Mann, Kazantzakis was a child of the fin de siècle; both writers detested the “sickliness” and “flabbiness” of nineteenth-century liberal-bourgeois civilization and yearned for a violent, decisive transformation that would remake the world. Although both mellowed in their later years and displayed varying degrees of remorse for their earlier contributions to the twentieth-century conflagration that found its basis in such apocalyptic views, it is telling that they vacillated so easily between the left and right on their political journeys. Kazantzakis’ politics tended to laud the form of cataclysm and renewal, apart from any content. Yet, like Mann, his ambivalence in political matters, despite its manifestations which are so off-putting today, is paradoxically the source of his artistic strength.

Literature as Contradiction and Cry

Kazantzakis’ life was an agon, the journey of an unsettled radical through the many contradictions of politics, religion, and the artistic life. His great value as a writer is that he enshrined these contradictions in his own narratives. These remain a profound source of reflection for contemporary religious faith at the intersection of social and political transformation.

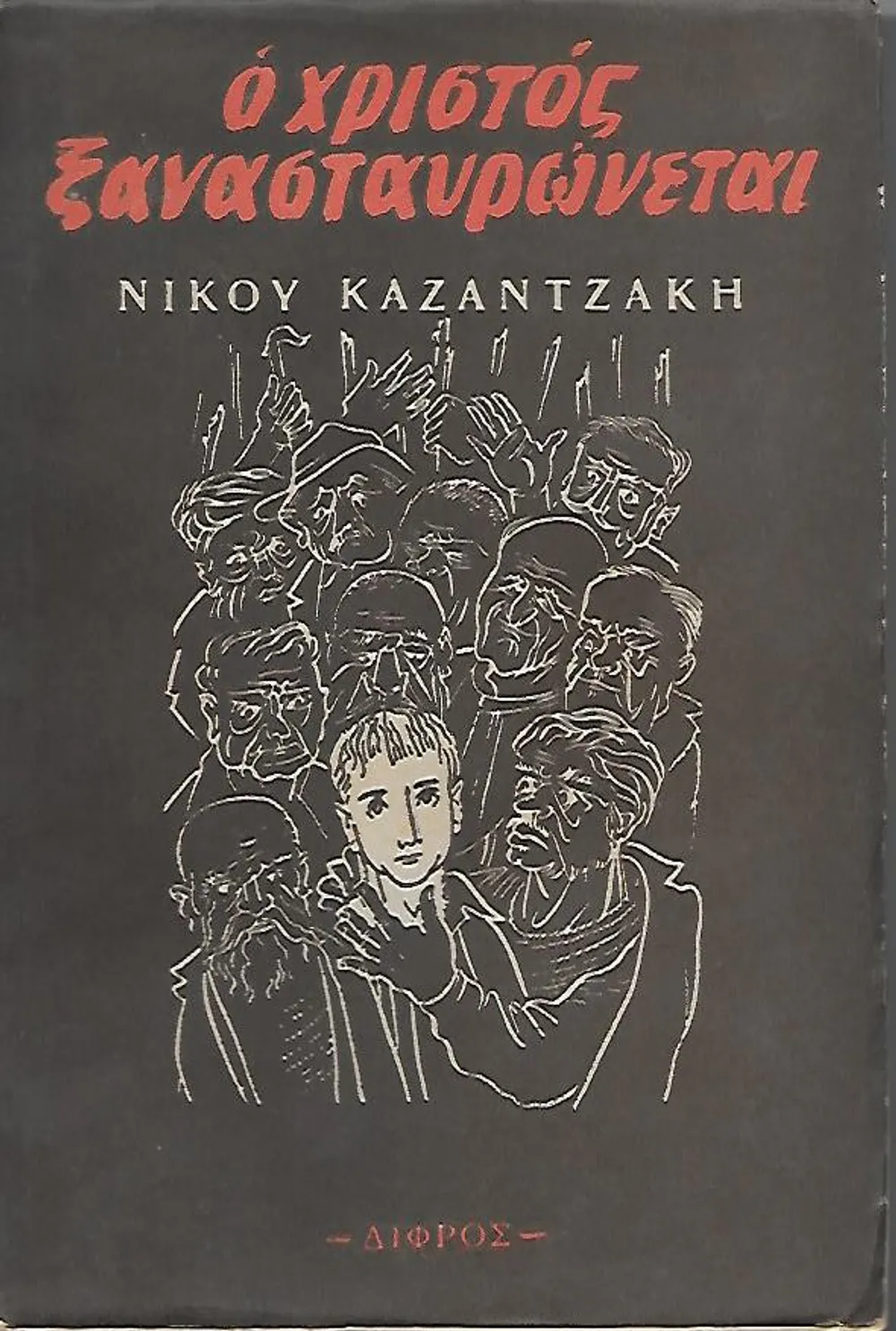

Christ Recrucified

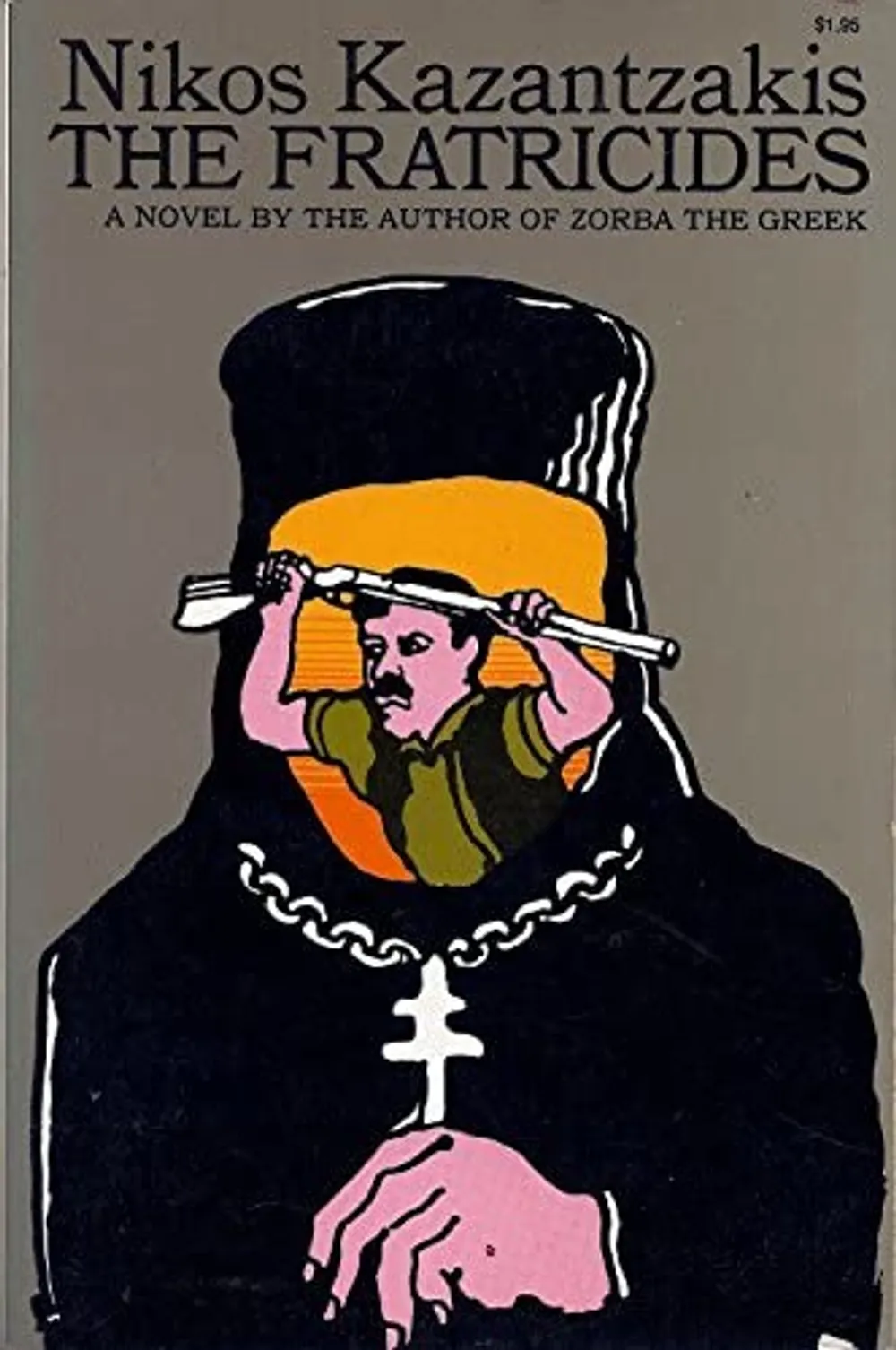

The Fratricides

Two novels in particular, both written in view of the Nazi occupation of Greece and the subsequent Greek Civil War (1943–1949), use Christ and Christian imagery to explore these themes, and it is on these that I want to focus rather than the more popular Last Temptation (whose Jesus is more concerned with religious belief as such and its corresponding psychological questions than with political questions). Christ Recrucified (composed in 1948, translated as The Greek Passion in English) and The Fratricides (composed in 1949) are mirrors of each other, the former wrapped in a mythical shell and the latter reduced to the bare elements of realism (a genre Kazantzakis otherwise detested), but both encompassing Kazantzakis’ political and spiritual preoccupations. Both feature Christ-like protagonists caught in the middle of a web of destruction: brother devouring brother, Greek fighting Greek, communists, nationalists, and apolitical bystanders all bent on self-annihilation. In these two novels, character and plot bring together all of Kazantzakis’ previous experiences and political fluctuations.

What happens in his art as a result is perhaps beyond even Kazantzakis’ control. Although he undoubtedly wished to inscribe the “lesson” of his philosophical commitments in his novels, the Christ figure complicates all easy readings. What is certain is that Christ is the figure who upends, who remakes, who stands exactly at the unbearable point of transition to a new age, the contradiction between present reality and future possibility.

As such, Christ is the embodiment of political and spiritual struggle, a figure whose actions represent a cry (kravgí) of solidarity with the broken world which is simultaneously a cry of desperation and hope. The cry was for Kazantzakis the only worthy artistic and spiritual act in a world that had crushed all material attempts to remake it; more than anything, it was his way of communicating to future generations of readers that they too must take up the urgency of the task that he and his generation could not complete.

The Four Great Pillars of the World

Christ Recrucified is a many-layered novel which at first appears to follow a simple schema. Lycóvrisi is a fictional village in Anatolia circa 1922, where Greeks live in uneasy subjection to their Ottoman rulers. The village is preparing an ambitious reenactment of the Passion for Holy Week, and its elders select villagers to incarnate the apostles—the shepherd Manoliós as Christ, the high-born Mihelís as John, the traveling merchant Yannakós as Peter, the cafe owner Kostandís as James. Almost immediately, these modest villagers inhabit their roles quite literally, sparking conflict with the elders, who, for their part, are drawn as caricatures of the deadly sins and represent the dominant institutions—the wrathful local Orthodox priest, Father Grigóris; the gluttonous hereditary archón Patriarchéas; the “arch-miser,” Ladás; the cowardly schoolmaster, Hadji-Nikolís.

The conflict between the groups quickly comes to a head with the arrival of Greek refugees to the village. Here the novel echoes an historical event that played a momentous role in Kazantzakis’ life. Since the Greek War of Independence in the early nineteenth century, irredentist nationalists had been motivated by the Megáli Idéa, the “Great Idea” that would restore the dominion of the Byzantine Empire by retaking “Greek” lands currently ruled by Turks. Foremost on the agenda was the recapture of the region of Anatolia (the Western part of modern Turkey).

The inflammatory rhetoric took on renewed significance after the First World War, when Allied support promised decisive action against the crumbling Ottoman Empire. The Greeks made inroads into Anatolia in 1919, sparking a war with the fledgling Turkish National Movement. Kazantzakis was firmly in the nationalist camp at this time in his life, but what happened in 1922 dealt an irreparable blow to the Megáli Idéa and is still considered the greatest catastrophe to befall modern Greece. Late in that year, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk drove across Anatolia and set fire to the city of Smyrna (İzmir), precipitating a wave of over one million refugees across the Mediterranean.

In Christ Recrucified, Kazantzakis uses the arrival of similar war-torn Greek refugees to Lycóvrisi as the impetus for the spiritual and political conflict that forms the core of the novel. On the meta level of Kazantzakis’ Bergsonian philosophy, Peter Bien reads the refugees as synonymous with the evolution of Spirit; they arrive at the beginning of the novel, endure a crucible, and continue on their way at the close, propelled in a never-ending transformation. Such a reading is strengthened by Kazantzakis’ identification with the leader of the refugees—the inspired but outsider priest Fótis, “unconquerable, great-souled”—who acts as a thematic counterpart to Manoliós’ Christ.

Fótis, whose name recalls the elemental “gladdening light” (Fόs Ilarόn) of the Orthodox vesper hymn, is Kazantzakis’ ideal Nietzschean hero, one who in full self-actualization battles with materiality and loses, and yet whose unbending witness allows the “transubstantiation of flesh into spirit” to continue unto further generations. Reading the novel purely as a philosophical exercise as Bien does, however, misses the pathos that arises from the novel’s structure and plot. These point to a deeper concern with the profoundly personal and spiritual nature of political struggle, where neighbor is set against neighbor.

Fótis and the refugees encamp on a mountain above the village, near a chapel of Elijah, the saint whose chariot of fire harmonizes with Fótis’ elemental light. Having been deprived of everything, they implore the village for simple necessities—food, shelter from the coming winter, land to sustain themselves—which all go ignored. At the midpoint of the novel, the elders, the group of apostles, the villagers, and the refugees all find themselves on the mountain during the festival of Elijah. There, the growing conflict is uncovered by Manoliós, who is transfigured into Christ in the eyes of the villagers.

Manoliós implores the villagers to follow the example of Christ—to clothe the poor and feed the hungry, to give a tenth of their labor to the refugees to sustain them—and wonders why belief in an eternal afterlife does not spur them to righteous action in this life. Their selfish attachment to material goods has caused them to blaspheme against Christ. The villagers are initially shocked, but they gradually come to realize that Manoliós is speaking the truth. The anxious elders try to interrupt this Sermon on the Mount and the spell being placed over the villagers, claiming:

“There’s nothing now but grievances, scandals, thefts. The poor have grown bold and wish to raise their heads, the rich cannot sleep.”

Against such impudence, the village priest, Father Grigóris, derides the crowd and cries:

“The world, remember, rests on four pillars. Along with faith, country, and honor, the fourth great pillar is property: don’t lay hands on it!” (260)

This scene is another familiar specter from Kazantzakis’ life. In the middle 1920s, when Kazantzakis considered himself a revolutionary communist and was becoming enamored with the Soviet experiment, his hometown of Iráklio on Crete was the setting for an almost verbatim exchange between the authorities and a group of radicals. After the defeat of Greek nationalism in Anatolia, many veterans returned home radicalized and tried to foment communist movements in local areas. It appears from biographical documents that Kazantzakis personally tutored a group of these communists, whom he lauded as true “fishers of men.” The incident turned into a public scandal when the local press denounced Kazantzakis and the group as “against worship of God, against respect for the family, against obedience to the law, against love of the fatherland, and against respect for private property.” Kazantzakis agreed, and derided the bourgeois morality that claimed Christian values but that was in reality “always the image and likeness of the class that dominates” (Bien vol. 1, 94).

Like Kazantzakis in Iráklio, the itinerant priest Fótis and the refugees are condemned as “Bolsheviks” for occupying a position outside the bourgeois order of religion, nation, honor, and property. And both accept the label insofar as it names the demand for “new foundations,” the making of a new spiritual humankind by tearing down the false idols of superficial morality and petrified values—a Nietzschean quality Kazantzakis ascribed specifically to Lenin.

In this sense, religion betrays its own radical instinct, substituting its origins based in material transformation for the comfortable hypocrisy of class position. This is the atheism that is an affront to the person of Christ. What is needed is the hammer of “Bolshevism” to break the hold of the “four great pillars of the world.” The novel’s true genius is that it imbues this theme with a mythic timelessness by layering multiple eras and places into one, superimposed narrative of radical social-religious struggle. I think that this layering device counteracts the unsavory Nietzschean undertones of Kazantzakis’ philosophy, and instead leaves us to grapple with the inherent contentiousness of the Gospel itself.

The Politics of the Passion

There are at least three spatio-temporal layers in Christ Recrucified. First, of course, there is the timeframe of the novel’s “mythic” base, the Gospels and the historical Jesus. Then there is the timeframe of the novel’s plot, which replicates the nationalist upswell of the Mediterranean in the 1920s. Finally, there is the timeframe of the novel’s composition—the era of the Greek Civil War two decades later, in which the Communist Party of Greece was effectively decimated by anti-communist Western forces. (Kazantzakis was publicly on the side of the losing Communists.) This contemporary event also forms the direct setting for the plot of the novel The Fratricides, which features another unruly priest named Yánaros.

Father Yánaros is pulled between the communist guerrillas holed up in the mountains and the anti-communist brigades that defend his town below. If the priest Fótis is the positive model of Kazantzakis’ philosophical-political Christ, Yánaros is the negative. Haunted by visions of “the Great Comforter Lenin” and the supersession of Christian faith by atheistic materialism, on the one hand, and the destructive nihilism of fascist anti-communism on the other, his futile kravgí for a world of justice and harmony ends in ineffectual silence.

Like Kazantzakis’ other Christs, Yánaros—who “looked at his guts and the guts of the world and was sickened”—also longs for the world to be purified, but, in the reverse Bergonsian formula, he is defeated by the downward-driving cycle of destructive matter that inhibits the upward motion of Spirit. Christ is recrucified here, too—just as the Megáli Idéa and Greek communism had been crushed—when Yánaros is murdered by the guerrillas on Easter in a brutally ironic scene. The pessimism of The Fratricides is a more accurate representation of Kazantzakis’ attitude toward political affairs by the late 1940s. For this Kazantzakis, no human philosophy or political program—and he had tried many—offered any hope of radical renewal. The only possibility of transformation was eschatological and apocalyptic.

However, this is not where the art itself stops. These two contemporary timeframes allowed Kazantzakis to speak directly to his own experience and the tumult of his own times, and thus they shed partial insight on his politics. But returning to the first timeframe of the Gospels themselves as it echoes in the novel Christ Recrucified reveals a latent radical hope, which perseveres despite Kazantzakis’ personal pessimism. I contend that, apart from Kazantzakis’ idiosyncratic philosophy, the mythic layering of Christ Recrucified invites us to understand the radical political implications of the Passion narrative itself, and how it resurfaces again and again as a symbol of social transformation.

The actions of the Christ-figures Manoliós and Fótis, and their confrontations with the reigning institutions of power, point to the inherently political shape of Jesus’ life and death. There is a common way of presenting this political aspect of the life of Jesus, especially in progressive discourse, that manages to be both anachronistic and reductive: according to this version, Jesus was a dark-skinned, first-century Palestinian who bravely resisted a hegemonic Empire through an act of rebellion. Although such a sloganized formulation may have limited use today for a politics of identity, it seems to me to mischaracterize the more complex and contradictory layers of the Gospel narrative. At the very least, it is liable to the ambiguity that characterizes identity: Jesus can be, and is, just as easily appropriated for chauvinistic nationalism on the Right. In contrast, Kazantzakis’ Christ narrows and at the same time deepens the frame.

For Kazantzakis, the real struggle the Gospels narrate is not of an abstract revolutionary against an abstract Empire—aptly symbolized and passed over in Christ Recrucified by the agha, the sanguine and Pontius Pilate-like Ottoman overruler of Lycóvrisi who cares nothing for the Greek refugee affair—nor is the struggle primarily religious. There is no separation between the religious and the political; both are united in an insistence on the destruction of the old and the birth of the new (another point of overlap between Christ and Lenin). Rather, the struggle occurs within the prevailing social reality, whose boundaries encompass the family, church, state, in fact all of everyday life: brother against brother, son against father, the faithful against the hypocritical, the radical against the ossified. This is the struggle of a normally invisible social reality with and against itself, not of a community with an outside force—and a struggle that breaks the occluding mists of ideology to take place out in the open.

The deeply personal questions of “who provides,” “who benefits,” and “who decides” the issues of material life—questions Manoliós and his disciples raise simply by taking on the plight of the refugees—are those which outline what can only be called a class struggle. If the figure of Christ can be adapted into any factional view, this is a Christ which lies beyond all such attempts and yet fundamentally embodies the cry of the poor. Not only the hypocrisy but also the futility of those who defend the “four pillars of the world” are revealed in the harsh light of Gospel truth. These are tied to the way of death, whereas Christ brings new life.

Christ is thus a paradox: in confronting the “class that dominates,” Christ appears as the true God who breaks the atheistic pillars of the world and reorients the people to divine justice. But in a striking dialectical reversal, it is precisely this confrontation which makes Christ himself the atheist from the standpoint of the four pillars—which is in fact the more compelling standpoint, because it is the one that arises from objective social relations anchored in history. (Remember also that the early Christians were accused of being atheists for refusing to worship the Imperial cult.) Despite their yearly Passion Play, the villagers of Lycóvrisi have in fact lived in subjection to the four pillars by virtue of their inherently oppressive class structure, of which religion is a major part. Christ is the social nexus where ideology is revealed as ideology; Christ is the one who transvaluates all values. In an unequal class society, that means Christ is necessarily a Bolshevik.

Further, this Christ consciously understands the enormous stakes of challenging the four pillars. Christ is not recrucified because of opposition to “the world” or to authority per se. Rather, Christ is put to death by leaders in his own community in retaliation for the fact that “the poor have grown bold” and have attacked the foundation of worldly power—because to attack the foundation is the Gospel. But what is being attacked is the reality of hate and domination itself, the destruction of which is the only way to release the cry, to end the division of class struggle, out of a commitment to a greater power. This calls to mind a saying by the great Dominican-Marxist priest, Herbert McCabe, as told by Terry Eagleton: “If you don’t love, you’re dead, and if you do, they’ll kill you.”

This is why Kazantzakis places the same bloody denouement of Christ Recrucified in a church, just as in The Fratricides. Things turn quickly for Manoliós when the authorities make a concerted effort to silence him after the refugees, emboldened by the incident on the mountain, decide to raid the village. Father Grigóris interrogates Manoliós in the village church on Christmas (the subtly altered counterpart to Easter in The Fratricides) while the crowd calls for his death. After repeated accusations of Bolshevism for his standing by the refugees, Manoliós answers: “If Bolshevik means what I have in my spirit, yes, I am a Bolshevik, Father; Christ and I are Bolsheviks.” In the following moments, Manoliós is lynched in the church by Christians. But unlike the bitter and pessimistic ending of The Fratricides, here the martyrdom allows Fótis and the refugees to escape. They have not succeeded in destroying the foundation of the old world, but they have not perished, either.

Kazantzakis Against Kazantzakis

What are we to make of Kazantzakis’ agonized writings? The novels are worth reading, although there is much in them to view critically. Kazantzakis placed a foolish hope in martyrdom for martyrdom’s sake; his Bergonism took St. Paul’s admonishment in 1 Corinthians literally: “the seed you sow does not germinate unless it dies.” Kazantzakis adopted a tragic outlook of politics because all of the factions he had participated in failed. He and his characters can only utter a kravgí, a blind cry of despair and hope, before being snuffed out. Their true hope is eschatological, and in that sense they are excused from the nightmare of history. Their only authentic action is to endure in the struggle that extends to future generations.

But as later readers of Kazantzakis, I think we are in a position to appreciate his art as a vessel that keeps the flame of radical, even utopian transformation alive. An eschatological horizon can impart a necessary goal toward which efforts at socialist transformation can strive, but it does not mean resignation to tragic endurance. Stasis and immobility is death, in politics as in religion, as the defenders of the four pillars evince. Against Kazantzakis’ own personal beliefs, the world is not remade in an instant or in an apocalyptic end to a “transitional age.” Rather, this remaking requires patient and active work to realize.

This is the power of Kazantzakis’ Christ: he is a figure who shows that this is a process that can be carried forth from within the seemingly closed and unquestionable system of the existing social fabric, drawing from past struggles and extending them to the future. This is a Christ who by his very nature is a contentious challenge to the atheism of the four pillars of the world, the forces that destroy and oppress life.