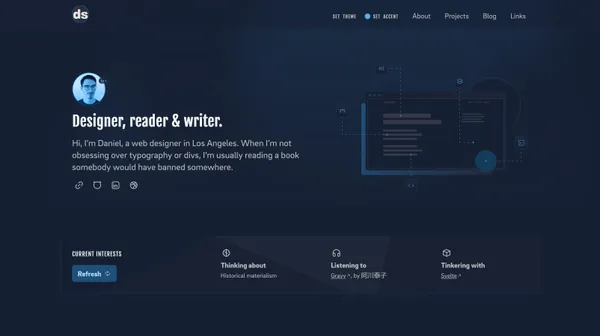

To ring in the new year, I'm excited to share a new version of this site with a fresh design, built with Deno Lume.

To ring in the new year, I'm excited to share a new version of this site with a fresh design, built with Deno Lume.

The final installment in this post series looks at building a dynamic front-end website for an Airtable reading tracker, using the Deno Fresh server-side rendering framework.

Using Airtable as a back-end to build out a custom reading tracker app.

An effective reading tracker would not only provide a chronological list of titles read, but would uncover the manifold associations of influence and interest that are constantly being formed from the books I read.

It is, I admit, something like a Puritan's envy for that cheerful and conciliatory user experience of the Mac that finally led me to forsake the dour Northern lands of PC-dom and to cross the operating-system Tiber.

Choosing the right typeface for a website or project is an inexact science that often seems wholly subjective or arbitrary. For me, it’s a mostly intuitive process that involves a lot of trial and error. But sometimes things just click.

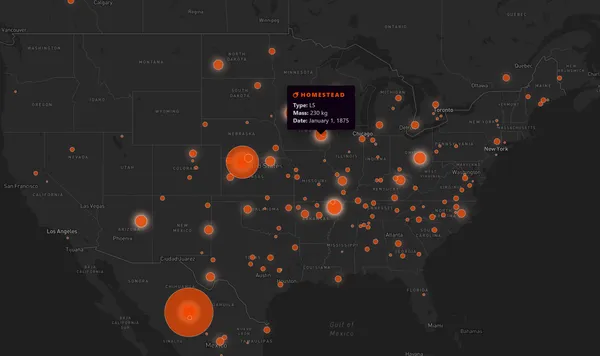

Playing around with the Mapbox GL JS API and plotting observed meteorite falls.

Using the Airtable hybrid spreadsheet-database app as a CMS "back-end" for a personal portfolio Jamstack website.

As tempting as it is to fantasize on what could have been, the historian’s task, Hobsbawm quips, is to analyze what was. And so despite his sympathies and disappointments, Hobsbawm does what no ideological historian can do, but which only the best Marxist thinkers are capable of.

Max Weber famously argued for an “elective affinity” between a Calvinist work ethic and the economic requirements of industrial capitalism. In its insistence on secularized vocation and deferment of worldly pleasure, according to Weber, the Protestant work ethic gave religious sanction to certain kinds of economic activity, namely, the reinvestment of wealth as capital to build society’s productive forces.

The music brings out this sense of inexorableness that the text signals with words like bestimmen (designate, determine, appoint) and the clipped, forceful, almost untranslatable Not (destitution, misery, dire need).

“Cardboard Darwinism,” writes biologist Stephen Jay Gould in an essay of the same name, “is a reductionist, one-way theory about the grafting of information from environment upon organism,” or what amounts to a form of biological determinism.

Shelving books is, in fact, a dialectical art. Against the rigid, metaphysical hierarchies of the Dewey Decimal System, the dialectical approach begins not with stale Platonic categories (“Philosophy,” “Art,” “Religion”) but with the understanding of the varied internal relations among books.

Walter Rodney’s rejection of rigid models of historical interpretation and “necessary” trajectories of socialist development transcends Cold War limitations. Instead, his authentic use of Marxist historical materialism impels him to begin, per Lenin, with the “concrete analysis of concrete conditions.”

Nothing could be the same in the world after 1917, for “what should never have been became real”—a society where the oppressed masses had overthrown the oppressing classes and where “a total change in the life of the people” was being made.

As a guide to understanding the cultural mythology and socio-geographical history of the singular American city that represents both “the utopia and dystopia for advanced capitalism,” there is none more incisive than Mike Davis’ City of Quartz.

If Marx focused so much on the material, it was because he found it integral to collective human flourishing in a sense similar to the Aristotelian eudamonia—physical, mental, and spiritual well-being achieved through practical activity.

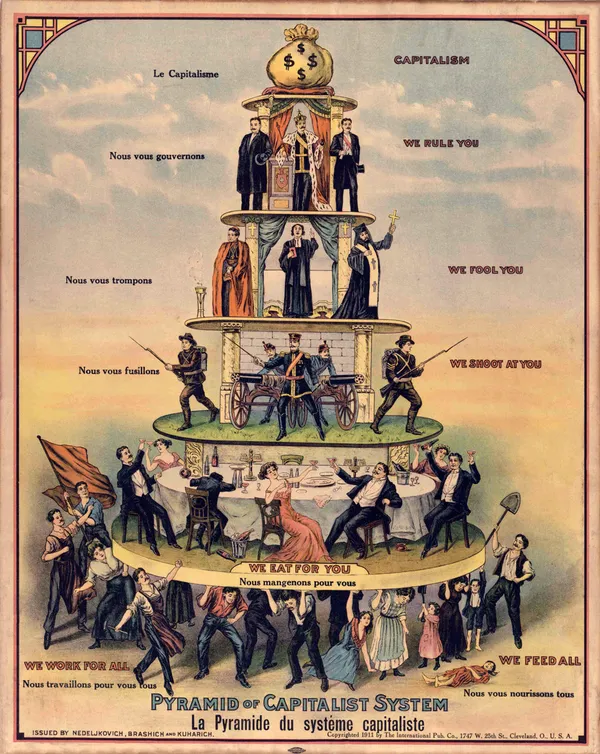

There is a story told about capitalism—mostly by its proponents: classical liberals, American conservatives, libertarians, and the like; but also sometimes inadvertently by its Marxist critics—that sees this system as synonymous with human nature in all times and all places.

Thomas’ “metaphysics,” if indeed it can be called that, is neither an overarching rationalist system nor a purely sense-oriented empiricism. Perhaps it is ultimately closer to the dialectical materialism of Karl Marx—a philosophy engaged with the flux of material, historical change and humanity’s common interaction with itself and nature—than it is to any Enlightenment idealism.

The cinema of David Lynch, true to the spirit of its Surrealist predecessors in art and film, has always resisted conventional characterization or description.

“In the person of Francis the premodern world, so to speak, gathered itself together before coming to an end. For one last time, before the forces of progress thundered off on their triumphant path, one man looked into the motivating thrust behind the whole thing and decisively rejected it: Francis of Assisi, the last Christian.”

Walking is a mode of living that embraces freedom, but this freedom is of a vastly different sort than that offered by the plethora of choices and dependencies that entangle us in the web of our consumerist lives.

In Rabelais and His World, the Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin argues that Rabelais is the culminating literary expression of the carnival or grotesque idiom of folk humor, an idiom which had developed for over a thousand years (starting with the Roman Saturnalia) as an “unofficial” or subversive culture in the West, complete with its own rites, rules, and symbols.