The Three Stages of Capitalist Space

What is postmodernism? By now, we all know that we’re in it and that there’s no getting out of it—even if, like all periods as they’re being experienced, we can’t exactly define it from the inside, without the benefit of hindsight (nor can we tell if we haven’t indeed progressed to something beyond, like “post-postmodernism”).

Getting at the heart of what and why postmodernism is remains a challenge that few thinkers have been able to face with as much brilliance and perspicacity as Fredric Jameson, notably in his Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991), which still reads as timely over 30 years later. Part of what makes this book great is that Jameson tackles not only postmodernism itself but also postmodernism theory—the two have become largely synonmyous, and not without reason, but there is a wealth of insight to be gained from questioning not only the form but also how we think about the form.

Aside: I recently read this book as part of an online course given by the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, a fantastic organization that makes the world of critical theory accessible to people outside the academy. I have taken a few courses with BISR and can’t recommend it enough for anyone interested in the intersection of culture, politics, and theory; for this book in particular, having a group of people to read and talk about it with was indispensable.

Postmodernism: Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

Very late in the book (410-418), Jameson offers a brief account of what he calls the “three stages of capitalist space,” which for me clarifies the preceding 400 pages of dense analysis and underscores how Jameson conceives the core elements of postmodernism.

(This is not the place to dwell on Jameson’s style, but suffice it to say that reading him is to experience a constant stream of mini-epiphanies; his sentences need to be read and re-read to do their work on you, and in a sense you cannot fully grasp them until the very end (of the sentence, paragraph, book), at which point you must circle back to start again with that knowledge to track the thrust of the argument. It is the very model of the dialectal method he wants to instill in his readers as a form of thought adequate to confronting the “totality” that characterizes the capitalist mode of production. This kind of writing, apart from being an exhilarating challenge, is meant to awaken us out of our “dogmatic slumber” of theoretical discourse into the very materiality of language and thought itself, to fold us back into the complexities of the world so we can better understand and change it.)

So, the “three stages of capitalist space”—for Jameson, this is the kind of “history by allegory” that he is so fond of; earlier in the book, he tells a similar version of this history, which he there frames specifically as a “myth” of periods of cultural production in modernity (95-96). That the concept of “myth” is the vehicle whereby we can trace the outline of the development of capitalist modernity—a covert, rather than frontal attack, philosophically speaking—is significant and clues us into the subtle operations of Jameson’s dialectical method.

For Jameson, it is through this kind of suggestive narrative that we get the most basic definition of postmodernism: it is the very form of late capitalism itself, the “mirror image” of our contemporary mode of production, which is different from but at the same time an outgrowth of capitalism’s previous stages. As this frame suggests, the spatial is another important allegory for Jameson, one that reveals how capital operates, is registered culturally, and is felt subjectively.

The cultural products or ideologies of postmodernism are thus not some free-floating, independent thing; they are intimately related to, indeed are alternative expressions of, the complex of forces that coalesce in that all-encompassing Marxist term, “mode of production.”

Another way of saying this is that everything is both material and ideological at the same time. This is very evidently so in the case of the “market,” which is both fundamentally an ideology (in the form of economic theory) and also a material reality (as a nexus of economic and social determinants), which resists and even shapes ideological concepts. This, then, is part of what Jameson (per Marx) means by a totality—an interlinked set of economic, social, cultural, and ideological forces that is quite a bit more nuanced and complex than the dogmatic “base” and “superstructure” of some vulgar Marxist explanations.

If there is an agent here, the subject of the narrative of modern history, it seems to be capital itself, and the driving force is its “universalizing logic,” which advances through each historical stage like a wind-borne wild yeast, leading to cultural productions which are like fermentations that differ according to time and place but are “caused” by the same agent. Jameson, like the Marxists of the Lukács-Frankfurt School lineage, at times refers to this force as reification—the process of everything falling under the totalizing logic of capital.

The postmodern can thus be characterized as that stage of capitalism where reification has reached saturation; the totality that Marx saw as constitutive of the capitalist mode of production at its nascent stage is now fully realized.

For Jameson, the only way through this murky narrative is the recovery of a critical historical faculty—something that appears to have dissolved in the postmodern, the period when we find ourselves unable to see the past as prelude to our present, or to see the present as our future’s past. On the last page of the book, Jameson finally shows his cards, and concludes with a clear and beautiful revelation of his method, one that characterizes his work as a whole:

The rhetorical strategy of the preceding pages has involved an experiment, namely the attempt to see whether by systematizing something that is resolutely unsystematic, and historicizing something that is resolutely ahistorical, one couldn’t outflank it and force a historical way at least of thinking about that. “We have to name the system”: This high point of the sixties finds an unexpected revival in the postmodernism debate. (418)

To that end, the following is my brief outline (not much more than a handful of notes) of Jameson’s own “three stages of capitalist space”—the historical narrative of capital as a mode of production (as distinct from ancient or feudal modes of production, for example), and as this mode of production comes to be expressed as postmodernism.

I am here using an experimental rubric which I call “Secularization,” “Structuration,” and “Saturation”; I’m playing around with the terms themselves (the second one in particular is not ideal), but as a first pass I think it accurately captures Jameson’s main thrust. (It should also be noted that most of the phrases and terms below are directly from Jameson.)

Within each of the three stages, the following themes serve to focus this exercise of “cognitive mapping”:

- Stage of capitalism: The particular nature of capital at this stage and how it operates as a variation of its own mode of production

- Spatial logic: A symbol for the re-organization of time and space that follows from the development of the mode of production

- Historical/cultural period: The stage’s relative position on the cultural-historical spectrum of “modernism” as a late-19th to mid-20th century phenomenon

- Cultural production: The characteristics of the art, literature, architecture, etc. that express the logic and spatial orientation of this stage

- Aporia: The stage’s “blind spot” on which its cultural production focuses, propelling it to the next form/stage

The Three Stages of Capitalist Space

Or, a journey toward reification.

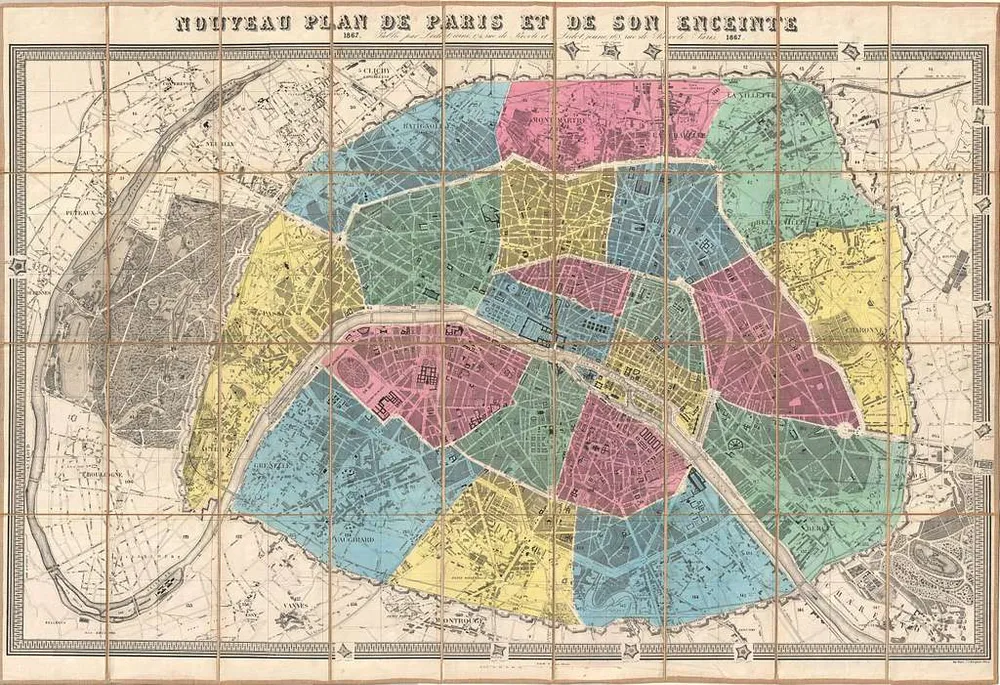

Secularization (Grid)

- Stage of capitalism: Classical (market) capitalism—the emergence of world markets and a system of production based on wage labor. “Exchange value” supersedes “use value” as the “goal” of production, leading to the inscription of universality and equivalence into the cycle of production, exchange, and distribution

- Spatial logic: Grid—the reorganization of sacred/primordial space into “geometric, Cartesian homogeneity.” Into this “space of infinite equivalence” is born the bourgeois subject and the ideological ideals of property and juridical rights—what Marx derided as “Freedom, Equality, Property, and Bentham.” In other words, the universal logic of the market begins to erode the uneven spaces of pre-modern and religious history; in its place, it sets up the ideals of freedom and equality, which are mirror images of the commodity form.

- Historical/cultural period: Enlightenment modernity, pre-modernism (mid-18th to late-19th century)

- Cultural production: The Enlightenment theme of demystification/desacralization; the “gap” left by the replacement of older ways of life by capital; the impulse to depict “real life” in the face of the ravages of industrialization and proletarianization, as expressed in the great realist artists (Zola, Balzac, Ibsen)

- Aporia: “Problems of figuration” in reconciling with the new spatial logic that only become apparent later; how socialism (as a triumph of Enlightenment ideals) is to be born in a world in the grip of capital.

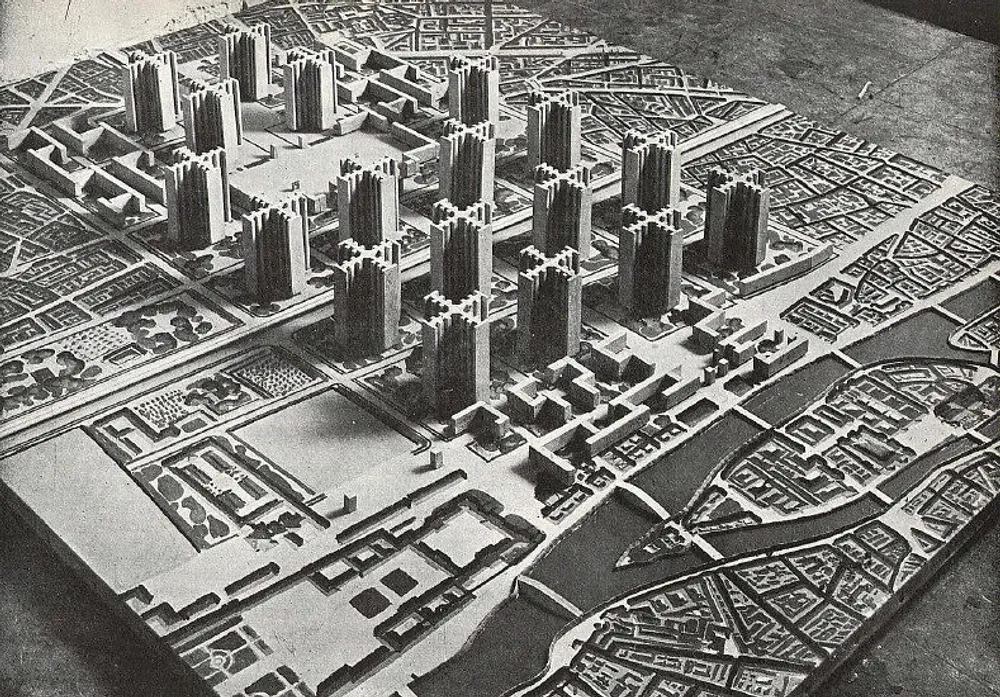

Structuration (Network)

- Stage of capitalism: The transition from market to monopoly capitalism—what Lenin called the imperialist stage of development. Capital extends over the globe at the same time that it is concentrated in the hands of a few national powers, leading to a vast interconnection of value chains.

- Spatial logic: Network—The ever-expanding “new colonial network” of the market and the media creates a contradiction between the lived experience of the individual and the massive structures that are emerging as subterannean drivers of social reality (and which are now revealed to have been there the whole time). This is a time of fracturing, of explosion, of the “age of the crisis of man,” of the old existing alongside the new, and of the global “uneven development” which reinforces colonial dependencies.

This dizzying parallax of experience prompts intellectual responses that seek to make sense of systemic complexity—Freudianism, existentialism, structuralism—but all of these still focus on the bourgeois individual and the subject’s misplacement in these structures (alienation). The Althusserian branch of Marxism attempts its own critique of these responses, but also remains indelibly tied to the framing of structuralism. - Historical/cultural period: High modernism (early to mid-20th century)

- Cultural production: Simultaneous existence or overlap of multiple temporalities (feudalism in the countryside, modernism in the cities), an unprecedented situation which leads to an emphasis on the Novum, a completely new way of being; Utopia as a literally realizable ideal in architectonic artistic “works,” which are suffused with an authorial will; figuration based on the dissolution of the “privatized middle-class life,” as bourgeois subjectivity is confronted with the strucutral complexity of the world system. From Joyce in literature to Le Corbusier in architecture to Picasso in painting; Pound’s exhortation to “make it new”.

- Aporia: Utopia as ultimately unrepresentable in art, which is the counterpart of the failure of 20th century state socialist projects; the paradox of “monadic relativism,” which Jameson describes thus—“a representation of the social totality now must take the (impossible) form of a coexistence of those sealed subjective worlds and their peculiar interaction, which is in reality a passage of ships in the night, a centrifugal movement of lines and planes that can never intersect” (in other words, art in the “in-between” land of ironic detachment, where no resolution of paradox is possible, a mood and technique perfected by masters like Thomas Mann).

Saturation (Quantum Field)

- Stage of capitalism: Late or neoliberal capitalism—the triumph of consumer society; capital in perpetual crisis and motion; the invasion of capital into all economic, social, and personal spheres (akin to what David Harvey calls the “spatial fix”); market capture of political governance; capital as subject of history.

- Spatial logic: Quantum Field—Jameson doesn’t use this term and I’m not confident I’m using it correctly either, but quantum theory is the closest analogy I could come up with for what Jameson describes as a “multidimensional set of radically discontinuous realities, whose frames range from the still surviving spaces of bourgeois life all the way to the unimaginable decentering of global capital itself…not even Einsteinian relativity…is capable of giving any kind of adequate figuration to this process” (412). Elsewhere in the book, Jameson describes this “hyerspace” as “smooth,” “reflective”, “saturated” (think glossy magazine photos or the Westin Bonaventure Hotel); it “suppresses distance” and maintains a multiplicity of overlapping and nested contexts that occupy the same space (think the Internet).

Like a quantum phenomeon, there is seemingly no external basis for its form; rather, it is in the fundamentally contradictory situation of creating its own ground of being. The effect of all this is to obliterate the formerly solid boundaries of the bourgeois subject and the diachronic sense of history; what emerges now is a fragmented subjectivity that knows only the immediacy of incompatible synchronicities, or in other words, the Deleuzian schizophrenic. The tools of structuralism appear to be no longer useful, because the foundation on which they stood no longer exists. - Historical/cultural period: Postmodernism (mid-20th to 21st century)

- Cultural production: The bulk of Jameson’s book is dedicated to exploring the characteristics of postmodernist cultural production, so I can only give a few brief highlights here. Besides the more well-known features or techniques of postmodernist art—pastiche, bricolage, play, imitation, deconstruction, relativism—Jameson focuses primarily on the concept of intertextuality (although he doesn’t like the term). In postmodernism, “works” have been replaced by “texts” (of any medium); unlike the terrible authorial burden of modernist works, the production of texts offers relief, because everything now is simply a comment on something else, rather than a radically new insertion into the stream of history.

In contrast to modernism’s obsession with temporality and Utopia, the brute force of the spatial itself here wins out: texts exist all at once in relation to all other texts; hiearchy gives way to precedence in an interminable series of which any element might be the starting point for a new series. There is no escape from the self-reflexivity of texts; everything ends up as an advertisement.

But this last concept of “wrapping” is probably the most interesting and potentially radical technique of postmodernist art. Jameson’s primary example here is of Frank Gehry’s house in Santa Monia, an “attempt to think a material thought,” in which a wall of hodgepodge materials literally wraps around a modernist suburban home. Regardless of the medium, successful wrapping pushes the boundaries of postmodern cliches at the same time that it recapitulates them—wrapping dissolves unities, opens up new vantages, and renews perception in potentially radical ways. - Aporia: To think the unthinkable thought, to systemize the unsystemizable, to renew historical analysis, to break out of “capitalist realism” with a renewal of revolutionary politics—goals shared by Marxist critique, science fiction novels, and other radical experiments challenging the boundaries of capitalism.