The Marx Delusion

Terry Eagleton’s witty Why Marx Was Right might more accurately be called something like: Marxism Is Not What Most People (viz. Those Who Have Strong Opinions on Marx but Have Probably Never Read Him) Think It Is.

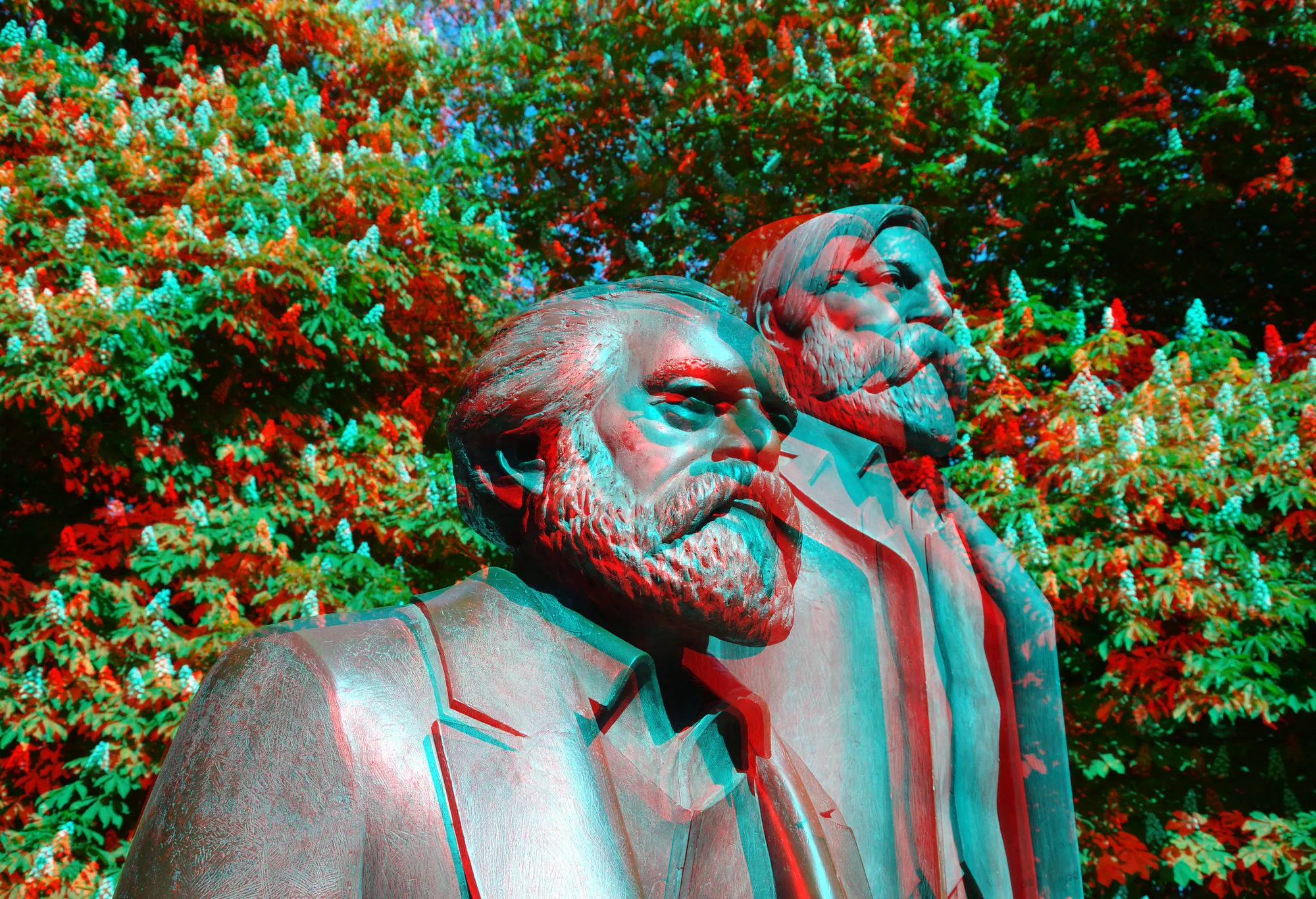

Or, What If the Common Objections to Marxism Don’t Have Anything to Do with Marx’s Actual Thought, which in Fact Constitutes a Plausible and Deeply Coherent Account of Life under Capitalism and which Is Still Relevant Today?, but in the interests of space and marketing, the chosen title is undoubtedly better. The perennial boogeyman of liberals, conservatives, and fascists alike, perhaps no thinker of such towering significance, Eagleton observes, has been so travestied as Marx.

We often hear, for instance, of Marx the determinist, the cold, Enlightenment rationalist who had no use for human freedom in his grand and inevitable scheme of dialectical materialism, as it marches ever onward to communist totalitarianism; Marx the anti-individualist, the eraser of personal and cultural identities in the grey, uniform sea of the vulgar masses; Marx the atheist, the militant secularist who wished for the annihilation of spirituality and the repressive opiate of organized religion; Marx the statist, the enabler of authoritarian regimes and bureaucratic tyranny; Marx the utopian idealist, a clueless dreamer who had no understanding of the practical considerations of governments or markets or human behavior (which is apparently nasty, brutish, short, and inherently geared toward greed and egotism); Marx the terrorist, the instigator of violent uprisings, perpetrator of class warfare, and enemy of decent, respectable methods of reform; and so on ad infinitum.

But none of these Marxes quite squares with the real philosopher from Trier, the humanist who inherited and built upon the Jewish themes of justice, liberation, and collective redemption; the passionate poet who quoted from Balzac, Shakespeare, and fairy tales in the pages of Capital; the German Romantic who despised the abstract and reveled in the concrete matter of existence—its blood, sweat, tears, and laughter. Nor do they accurately portray the views of a man for whom the state was “nothing but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie” (The Communist Manifesto) and for whom the utopian socialists like Saint-Simon and Fourier were pedants blinded by “their fanatical and superstitious belief in the miraculous effects of their social science” in attempts “to realize (their) castles in the air” (ibid.).

“Materialism for Marx meant starting from what human beings actually were, rather than from some shadowy ideal to which we could aspire,” writes Eagleton, a statement which ought to reassure any conservative wary of social planning and progressivism. Marx’s materialism, in fact, is one of his most misunderstood ideas—which is unfortunate, given that it forms the bedrock of his thought.

Far from being an atheistic monism “which regards matter as the only reality in the world…and which thus denies the existence of God and the soul” (the Catholic Encyclopedia), materialism for Marx is an argument for how history should be read—that is, precisely as the record of our activity first and foremost as self-determining, laboring, corporeal beings with material needs, rather than as the esoteric unfolding of Hegel’s “world spirit.” It is not so much an overarching system as it is a “theory of how historical animals function” and a call to examine a facet of societal development that is usually overlooked. Thought—including morality, law, and even spirituality—is not some disembodied, dualistic affair but is intimately bound up with our bodies and material context.

A thinker like Locke or Hume starts with the senses; Marx, by contrast, asks where the senses themselves come from. And the answer goes something like this. Our biological needs are the foundation of history. We have a history because we are creatures of lack, and in that sense history is natural to us. Nature and history are in Marx’s view sides of the same coin…

We can fulfill our natural needs only by social means—by collectively producing our means of production. And this then gives rise to other needs, which in turn gives rise to others. But at the root of all this, which we know as culture, history or civilisation, lies the needy human body and its material conditions. This is just another way of saying that the economic is the foundation of our life together. It is the vital link between the biological and the social.

As Eagleton notes in another of his books on the subject, Materialism, this foundational outlook of Marx’s is quite compatible with a sacramental religion in which God entered into this same material context to enact a historical mission, as well as with St. Thomas Aquinas’ conception of the human as an impermanent creature radically dependent on a sustaining Creator. It does not negate the spiritual but sees it as inseparable from the concrete facts of material existence.

If Marx focused so much on the material, it was because he found it integral to collective human flourishing in a sense similar to the Aristotelian eudamonia—physical, mental, and spiritual well-being achieved through practical activity. As Walter Benjamin wrote, “the class struggle…is a fight for the crude and material things without which no refined and spiritual things could exist” (Illuminations).