Building Myself a Reading Tracker App with Airtable and Deno Fresh, Part 2

As is evident from this blog, I’m a big fan of Airtable, and so as I set out to build myself a custom reading tracker, it was naturally my first choice for a hybrid back-end/administrative interface to use for a custom reading tracker.

Airtable’s friendly UI makes structuring relational data fast and easy, and its support for automations, scripting, and webhooks, as well as its robust API, means that you can make it the backbone of sophisticated custom apps. This combination of customization, ease-of-use, and web interoperability makes it almost too good to be true for this type of scenario.

Et tu, Airtable?

Well, it turns out “too good to be true” is pretty accurate, because Airtable knows how powerful their platform is, and apparently they don’t believe this power should be wielded by mere individuals. (Incipit rant—feel free to skip ahead.) As I was working on this project and writing this series of posts, Airtable rolled out a new pricing structure that effectively quashes hobby use-cases like this.

Previously, the free plan gave you access to scripting and unlimited API calls; on the new free plan, however, scripting and indeed all of the dozens of extensions (like base-wide searching and schema visualizations) have been removed, and API calls have been severely limited (from unlimited to 1,000/month). The next plan up which unlocks these features is now a steep $24/month.

This all feels like corporate arbitrariness (and greed) designed to cater to business teams/enterprise users. In a way, I get it; the free model seems ultimately untenable for fast-growing services like this. But it’s a weird feeling when you can tell a product doesn’t want you to use its product.

Luckily, I have a paid Airtable plan that I use for other work-related bases, and so I was able to retain the full power of my reading tracker setup. But it’s disappointing, not to say extremely frustrating, that this is the new reality. It now means that the setup I share below (as well as similar setups I’ve written about) is not replicable unless you have a paid plan. Had I started this project after the pricing restructure, I might have opted instead to use something else out of principle—but alas. Never lean too hard on a corporate service. (Or maybe it’s time to just dive full-on into SQL and relational databases…)

Base and Table Setup

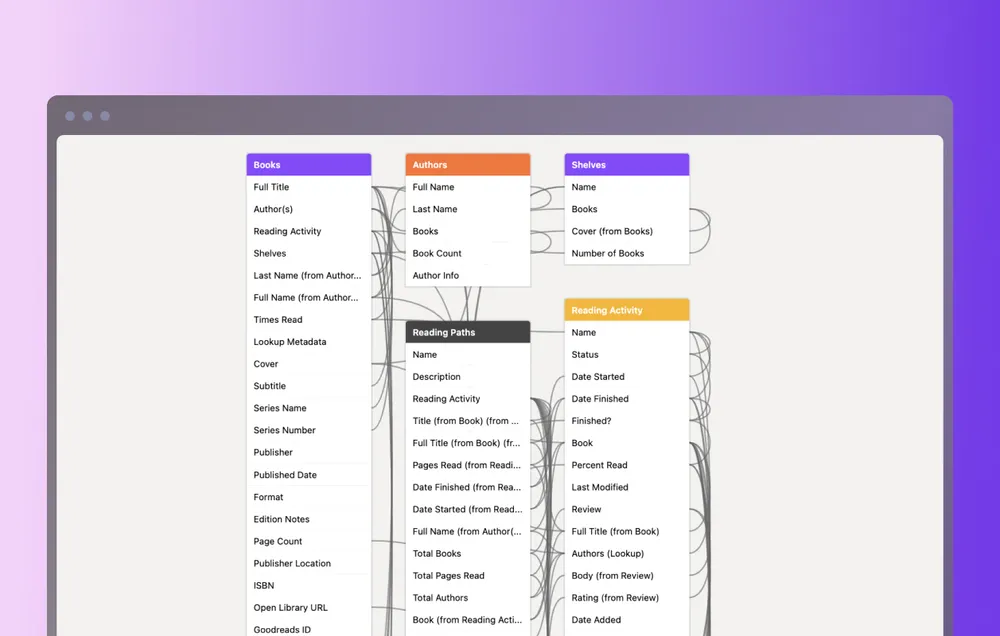

All that said, Airtable works really well as a database for tracking reading activity. Within the base, I have a number of tables set up for each type of data I want to track; this granular approach means that a record in any table can be associated in various ways with any the others. Book records can be a part of author and shelf records, but they also are a part of reading activity records.

Here is a breakdown of tables in the base:

- Books. As might be expected, this is the core building block of the reading tracker—everything starts with a book. Fields include basic book information like title, cover, and publisher, as well as other metadata like page count, format, series, ISBN number, edition notes, etc. (more on getting those below). Connected fields linked to other tables include authors, shelves, and reading activity instances. This allows for some other interesting metadata to be calculated using Airtable’s “rollup” fields, like “belongs to (x) number of shelves” and “(x) times read”.

- Authors. Pretty straightforward (at least for now), showing author records with simply a name and linked books.

- Shelves. Shelves are low-level tags grouping associated books. I’m trying not to be too precious with these, adding records of anything and everything that might be an interesting grouping: biography, capitalism, European literature, sci-fi, etc.

- Reading Activity. A reading activity record marks every “instance” of an interaction with a book, so one book can have many activities on it. This is one of the secrets of working with relational data; it might make sense at first to track this information directly on book records themselves. But separating out a new table with distinct fields gives you much more control and flexibility when dealing with the data. Fields on a reading activity record include status (read next, currently reading, have read), date started/finished, and pages read. Because this table can “look into” fields on the associated book records, I can also calculate other items like “percentage read” to see whether or not a book was finished (if percentage read equals 100%) or just “read” in any form (if percentage read is less than 100%).

- Reviews. Reviews are linked to reading activity instances and not books themselves, with the reasoning that thoughts and reactions to a book are highly specific to the time and place the book was encountered. This lets reviews be a snapshot in time, with the ability to add new or updated views on the book on subsequent reading instances.

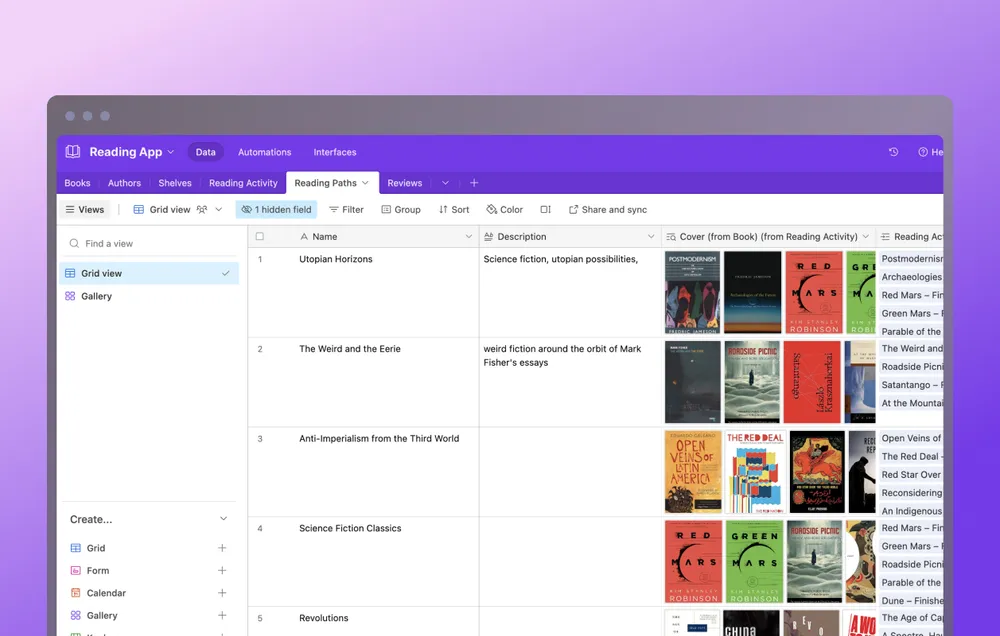

- Reading Paths. Finally, there is the reading paths table, which, as I mentioned in the first post, is my favorite table because it opens up really exciting connections between the books I’m reading. Each record in a reading path is like a “meta shelf,” a broad theme that either was set in an intentional reading plan or has emerged organically from the reading of the books themselves. The paths not only group books together, like a shelf does, but they also track the dates of interaction as linked from the activity instances. A path then becomes a chronological journal of how and when books have influenced the reading of other books—a shelf through time, as it were. Some examples of paths I have identified and named include “Utopian Horizons” (philosophical investigations of utopia and its possibilities in sci-fi and other literature) and “Smog City” (radical histories and stories of Los Angeles).

Getting Public Book Data

When it comes to actually populating the base with records, one option, of course, is to do so manually. There is a certain meditativeness for me in actually pulling a book of a shelf, looking through it, and adding information to a record. But as far as possible it would be great if most of this already-existing data could come from somewhere. And so in the programming spirit of “how can I spend hours figuring out a way to automate a process that might only take a few extra seconds anyway,” I set about trying to hack together a book metadata fetcher to build into the Airtable base.

The first and biggest problem was to find a reliable, open-source database or API from which to get the data. As I mentioned in the last post, Goodreads took their API offline years ago, so that route was closed, and the only other option I knew of was the Google Books API. That initially seemed like a good solution, but I ultimately decided against it because (1) it’s Google and also because (2) it was overly complicated and inconsistent. Searching for a book might return one of many different editions, each with its own idiosyncratic (and sometimes conflicting!) data—a fact you may have experienced if you’ve ever perused the Google Books previewer from search results.

I was about to give up hope when I stumbled upon Open Library, which is an initiative of the Internet Archive. While far from perfect (anyone can contribute to it, so it still has a lot of the same consistency and missing data issues), the Open Library Books API provides access to a lot of the book data I wanted and is really easy to use. (The Internet Archive remains undefeated.)

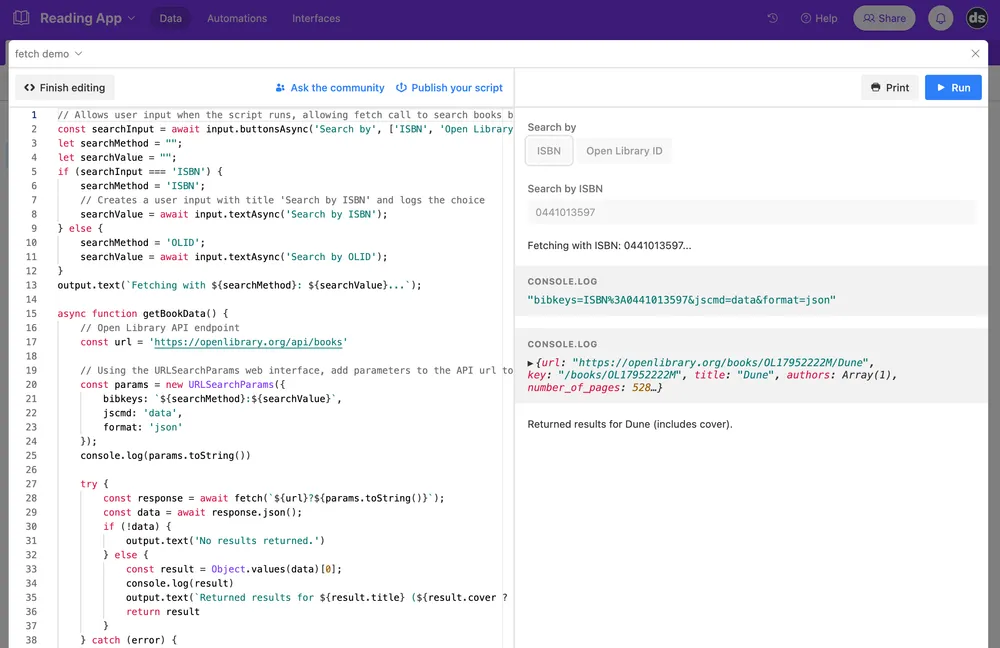

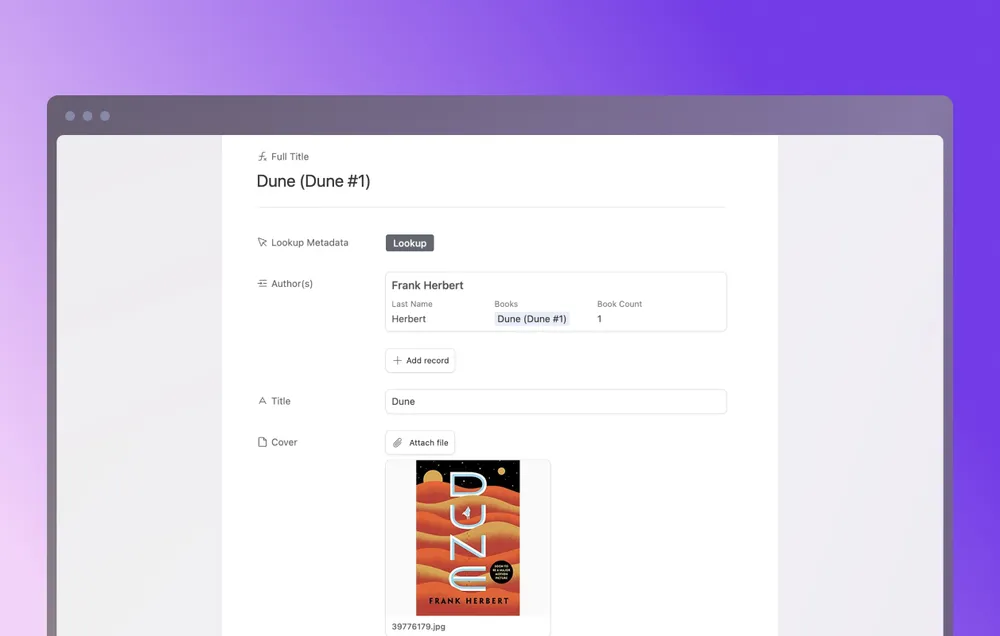

To incorporate this API into my Airtable base, I wrote a script to run a web fetch request to Open Library and save the returned data to various fields in Airtable. The script is attached to a button field in the Books table with the title “Lookup Metadata” and runs when clicked. Here is a look at the first part of the script:

// Airtable's scripting extension has an interface which allows user input

// through text, buttons, and selections, and which can output data as well.

// The first line presents a choice of button options to search books by ISBN

// number or Open Library's ID system, and saves it to a variable 'searchInput'.

const searchInput = await input.buttonsAsync("Search by", [

"ISBN",

"Open Library ID",

]);

// Initialize variables to hold the user selection so we can use it

// in the fetch call.

let searchMethod = "";

let searchValue = "";

if (searchInput === "ISBN") {

searchMethod = "ISBN";

// Captures user text input and logs/saves the choice.

searchValue = await input.textAsync("Search by ISBN");

} else {

searchMethod = "OLID";

searchValue = await input.textAsync("Search by OLID");

}

output.text(`Fetching with ${searchMethod}: ${searchValue}...`);

// Function to fetch the data.

async function getBookData() {

const url = "https://openlibrary.org/api/books";

// Using the URLSearchParams web interface, add parameters to the API url

// to filter the data requested. The interface constructor will return an

// object that will automatically encode the proper URL components for us,

// as shown in the console.log().

const params = new URLSearchParams({

bibkeys: `${searchMethod}:${searchValue}`,

jscmd: "data", // Format specified by Open Books to return book data.

format: "json",

});

console.log(params.toString());

// Example log: "bibkeys=ISBN%3A0441013597&jscmd=data&format=json"

// Try getting the data using fetch().

try {

const response = await fetch(`${url}?${params.toString()}`);

const data = await response.json();

if (!data) {

output.text("No results returned - check the inputs.");

} else {

// The API returns an object with the key being the ISBN, which

// is a bit unwieldy - extract this to a variable.

const result = Object.values(data)[0];

// Lets the user know the title of the result that was found

// and if there is a cover image in the returned metadata or not.

output.text(

`Returned results for ${result.title} (${

result.cover ? "includes cover" : "no cover"

}).`

);

return result;

}

} catch (error) {

console.log("Error fetching data:", error);

}

}

// Call the function.

const book = await getBookData();

// Sample return object:

// {

// url: 'https://openlibrary.org/books/OL17952222M/Dune',

// title: 'Dune',

// authors: Array(1),

// number_of_pages: 528,

// publish_date: '2005',

// cover: Object,

// ...etc

// }

This works pretty well and usually provides enough of a start for getting all the fields I want—especially the book covers, which saves some time having to look them up.

The second part of the script takes the returned data and maps it onto the appropriate fields in the Books table, using some of Airtable’s helper methods.

// Exit if no data is fetched or nothing is returned.

if (!book || Object.keys(book).length === 0) {

output.text("Record not populated.");

} else {

// First, get the Books table in our base.

const booksTable = base.getTable("Books");

// Second, get the currently selected record that the 'lookup metadata'

// button was clicked on.

const thisRecord = await input.recordAsync("Select record", booksTable);

// This function (not shown) does some logic to see if the main author

// attached to the Open Library result (always an array) matches an

// author that already exists in the authors table. If it doesn’t exist,

// it creates a new author record and returns the Airtable record.

const linkedAuthor = await getLinkedAuthor(book.authors[0].name);

// Update the current record's fields with the fetched data

// and any linked author record.

await booksTable.updateRecordAsync(thisRecord.id, {

Title: book.title,

Cover: book.cover && [{ url: book.cover.large || book.cover.medium }],

"Author(s)": [{ id: linkedAuthor.id }],

"Page Count": book.number_of_pages,

"Publish Date": book.publish_date,

// etc.

});

output.text("Record populated.");

}

To the Front-End

In the next post, I’ll look at how I used the Deno Fresh framework to build a server-side-rendered front-end to visually display all the reading data.