Aquinas and the Role of the Metaphysician

Part of modern philosophy’s distrust of metaphysics arises from a not undue association of the term with the Rationalist and Idealist philosophers of previous centuries; for thinkers from Spinoza to Hegel the task of metaphysics involves the deduction of an all-encompassing system of reality based on self-evident, a priori propositions, an activity which easily slips into speculation.

For Thomas, however, as F.C. Copleston argues in his gloss on the philosopher, the metaphysician is concerned with a very different kind of activity, one which is empirically rooted in our everyday sense-experience:

This point [that we cannot deduce from purely metaphysical premises the hypotheses and conclusions of the sciences] can be made clearer by anticipating to a certain extent and drawing attention to Aquinas’ general conception of the metaphysician’s activity. The latter is concerned with interpreting and understanding the data of experience; and to this extent the root-impulse of his mind is common to himself and the scientist. But the metaphysician concerns himself primarily with things considered in their widest and most general aspect, namely as beings or things. For Aquinas he directs his attention above all to things as existing; it is their existence on which he rivets his gaze and which he tries to understand. And this is one reason why Aquinas says, as we shall see later, that the whole of metaphysics is directed towards the knowledge of God.…

We can see therefore that for Aquinas the philosopher as such has no privileged access to a sphere of experience from which non-philosophers are debarred. His insight into the intelligible structure of the world presented in experience is the result of reflection on data of experience and of insight into those data which are in principle data of experience for everyone, whether he is a philosopher or not…. The ordinary man apprehends in some sense the fundamental metaphysical principles, though he does not formulate them in the abstract way in which they are formulated by the philosopher. It is so often the case that the philosopher makes explicit what is implicitly known by people in general.

This is Thomas as the “philosopher of common sense”—a term meaning not a kind of simplistic perception but rather knowledge building on the experiences that all people theoretically hold in common. For Thomas, everyone by virtue of their rational human nature has an intuitive understanding of things like universal terms, causality, and development; it remains to the philosopher to speak of them explicitly, often in new language so as to go deeper into what and more importantly why they are.

For ultimately metaphysics is concerned with “accounting for or explaining the existence of things which change and which come into being and pass away.” Experience shows us that the world, in its very finiteness and contingency, is subject to development and change. Philosophic reflection on this point leads us then to the opposite; that the things of experience, the entirety of the world as we receive it through our senses, are existentially dependent on something permanent, infinite, and unchangeable—for Thomas, this something is a Creator.

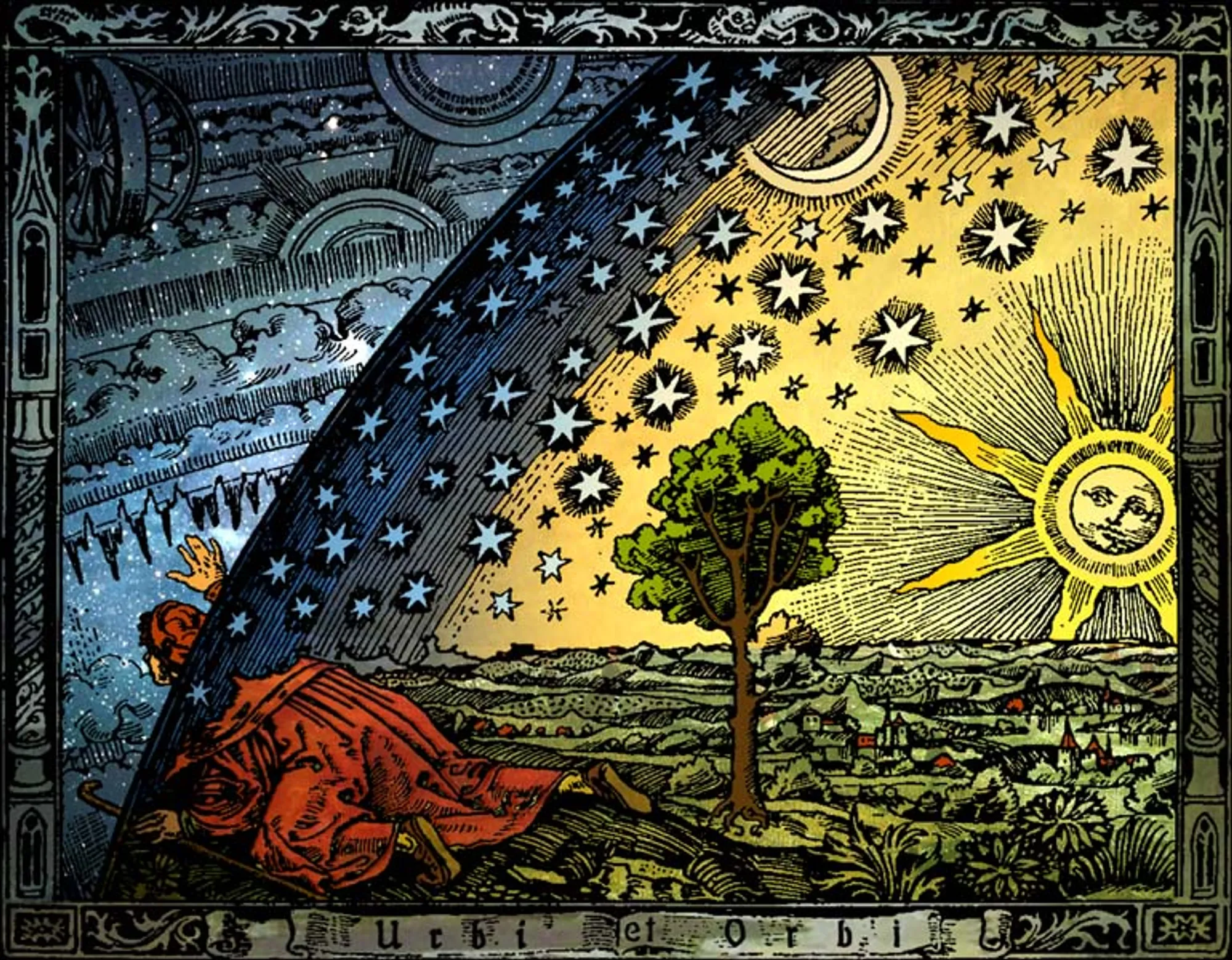

In this conception, the task of the metaphysician is never complete. While the truths uncovered by the metaphysician start to coalesce into universal and necessary forms, the metaphysician is always going out into the world to explore all of experience, constantly gathering data in a search for knowledge that is a mere waypoint on the path to the First Cause of all being.

Such a “metaphysics,” if indeed it can be called that, is neither an overarching rationalist system nor a purely sense-oriented empiricism. Perhaps it is ultimately closer to the dialectical materialism of Karl Marx—a philosophy engaged with the flux of material, historical change and humanity’s common interaction with itself and nature—than it is to any Enlightenment idealism.