Sounding Silence

It was the moment of the concert program that we all anticipated, one that would be sure to transfix the audience—the moment our college choir, each night on a trip through Europe, would sing Arvo Pärt’s radiant Magnificat (1989).

Back in our bare rehearsal room, as we stumbled through the music, familiarizing ourselves with its striking tonality, pathos, coherence, the piece lay dormant. But here, in the spacious cavern of Coventry Cathedral, in the cramped baptistry of an Orthodox chapel outside of Moscow, in worship halls from England to Russia, it burst forth, its true essence revealed. Like most of Pärt’s music, the Magnificat blooms out of darkness and exists in close relationship with silence. It captures the unbearable burden of the world, its grief and brokenness, while at the same time sounding an unmistakable note of pure, unwavering hope.

In the introduction to Arvo Pärt: Out of Silence, theologian and musician Peter Bouteneff notes that the tendency to describe first encounters with Pärt grows out of his music’s singular, transformative quality—an evocative spirituality that has captivated believer and non-believer alike. Bouteneff’s own first encounter was with the man himself, when both happened to be visiting the same monastery. Bouteneff knew nothing of Pärt’s music at the time; later, however, after hearing a performance of Pärt’s groundbreaking Passio (1982), he recalls beginning “a new relationship with music, a heightened understanding of the possibilities of art.”

Those familiar with Pärt most likely share a similar experience. What is it about Pärt’s music that has inspired this response in so many, and has led to Pärt becoming one of the most performed composers in the contemporary classical world? And what in the universal spirituality present in Pärt’s works can be supplemented by insights from Pärt’s own religious tradition, an ecumenical but firmly rooted Eastern Orthodoxy?

These are the questions at the heart of Bouteneff’s book, a product of the recently established Arvo Pärt Project at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary. Bouteneff does not write for an esoteric audience, and so much of the book will be a familiar recapitulation for those who have spent some time with Pärt. But newcomers and fans of all stripes will find in Bouteneff a fitting, lucid guide who tells a cohesive narrative with little recourse to technical language. This is the first book on Pärt to take a sustained look at the ways in which theology informs and surrounds his music, and here Bouteneff avoids positing a direct causal link between doctrine and art. Pärt’s music is not simply Eastern Orthodoxy relocated to the soundscape; one could compose in the same style as Pärt without sharing his religious background. In the same way, it is not necessary to be aware of Pärt’s Orthodoxy to appreciate the transcendent beauty of his music, as is evidenced by the many avid Pärt listeners who claim no religious affiliation.

Bouteneff’s book, however, is an argument for the strong correlation between Pärt’s deep faith and unique music, between the music’s substance and form. This confluence, channeled through Pärt’s own particular compositional sensibilities, is what makes him one of the most compelling composers alive today. Text, faith, and music exist together, in constant dialogue with each other. A deeper look into both can only enhance the listener’s experience, drawing out new revelations and resonant meanings. As Pärt’s wife Nora—one of his most lucid interpreters—has aptly framed it: “To really understand his music, you must first understand how this religious tradition flows through him.”

The story of Arvo Pärt’s musical conversion, which is closely connected to his religious conversion, is now legendary. During the 1950s, Pärt enrolled at the Tallinn Conservatory in his native Estonia (then under Soviet occupation) to train in the serial method, a form popularized by Arnold Schönberg, paragon of modernism in Western music. In place of the “hierarchies” of classical tonal music, Schönberg developed the planned cacophony of his twelve-tone technique, a system in which every note of the chromatic scale is equal to every other. In Schönberg’s serialism, atonal discord prompts in the listener feelings of dread, confusion, and chaos. The world is represented not as a rational cosmos but as an existential uncertainty. This is the testament to the collapse of presumptuous Enlightenment rationality, to the horrors of two world wars.

Pärt eventually felt the spiritual and musical burden of this compositional form, as is evident in later serial works like Collage über B-A-C-H (1964) and Credo (1968)—in which passages of turbulent atonality vie with sublime quotations from Bach. He reached a breaking point after barely a decade of composing, feeling that he had exhausted all the possibilities of serialism and that serialism had exhausted him. For eight years he was almost completely silent as an artist. What was Pärt up to during this time? In a way, he was going back to both musical and spiritual beginnings, to the epiphany of “a single note beautifully played,” in the composer’s own characteristically perceptive words.

Pärt began studying sacred texts, mostly those which have formed a bulk of Western classical music, but also the Church Fathers and the Philokalia. He read the Psalms and listened to early polyphonic masters like Ockeghem and Josquin. He studied the open, spirit-filled, yet disciplined contours of Gregorian chant. At the same time, he was being drawn into the orbit of the Orthodox Church. The unifying element in all of these pursuits was a disposition oriented toward the inner language and posture of prayer.

In direct opposition to the modernist penchant for excess and despair, Pärt was searching for purity, stillness, and unity, using the past to revitalize the present. He came to see the composer’s role as one of midwife, “drawing music gently out of silence and emptiness.” The music that emerged is of a kind with this silence, as the essence of a fully-grown tree is contained within its seed. Lest anyone take him too seriously, he disclaimed analogies to monk or prophet. Instead, he was like a child, newly come to the wonder of the world.

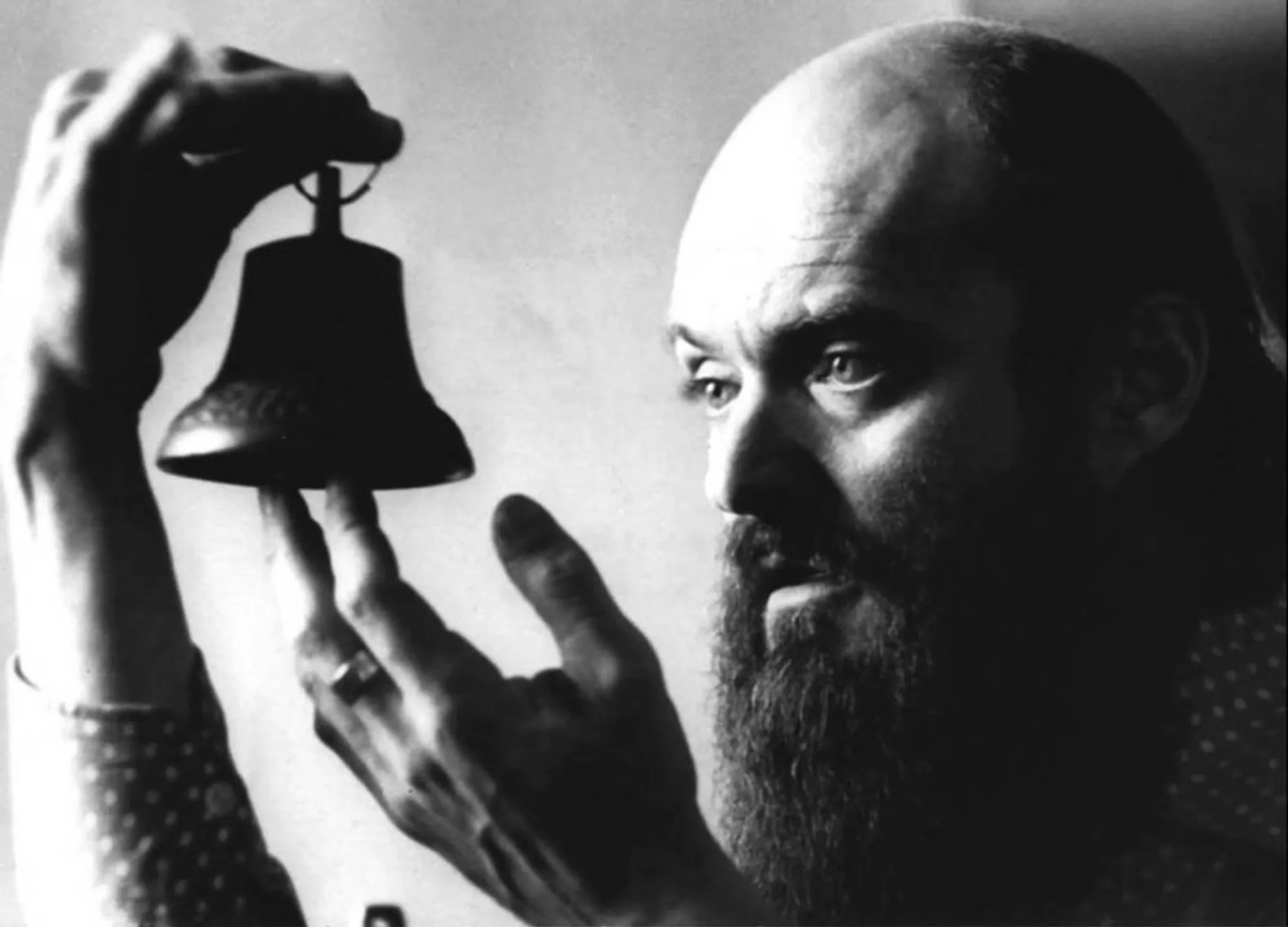

From this chrysalis of artistic silence was born Pärt’s distinctive compositional form. Its essence is two voices: one tonal, simple, and “objective,” and the other wandering, more complex, and “subjective.” The first voice is built on the most basic of musical constructions, the triad, which avant-garde modernism had largely discarded as antiquated but which Pärt used with compelling brilliance. The triad’s bell-like clarity and resonance gave Pärt the name for this compositional form, tintinnabuli. This first voice sustains, converses with, and occasionally opposes the second voice, which resembles the flow of chant. Stability and movement, the timeless and time-bound, the immutable and mutable—people have characterized these two voices in various ways, from divine providence and human sinfulness to Jiminy Cricket and Pinocchio (see the Icelandic singer Björk’s TV interview with Pärt). Always, however, these two voices are inextricable. As Bouteneff writes, their “net result” is an ongoing “relationship of tension and resolution,” an interdependency of being. The formula recalls the mathematics of the Trinity: in tintinnabuli pieces, “1 + 1 = 1.”

So far, at least to the non-musician, this may seem a bit abstract. But for most listeners, there is also an immediate, visceral quality to Pärt’s music, one Bouteneff aligns with the concept of “bright sadness.” The term comes from the Greek harmolypi—joyful sorrow, hope in the midst of despair, an acknowledgement of suffering that retains an assurance of healing. It is this quality which seems to resonate most with all listeners of Pärt, and yet it is also one which has deepest roots in the Christian, specifically Orthodox, tradition.

Here Bouteneff offers a promising contribution to future studies on Pärt. He traces the theme of bright sadness from biblical texts (Adam’s expulsion from the garden, the Psalms, the Passion narrative) through the Desert Fathers and Mothers and up to more recent figures like St. Silouan, a Russian who joined the Orthodox monastery at Mount Athos in 1892. Silouan has been a kind of patron saint for Pärt. A portion of Adam’s Lament, Silouan’s extended meditation on Adam’s grief over the loss of paradise, was set by Pärt in 2010. Silouan’s exhortation to “keep thy mind in hell, and despair not,” might sound absurd in an age of anesthetization, but it is a posture which is unafraid both to stand wakefully in the midst of the world’s fallenness and to hope in its redemption. Silence is not the silence of God’s absence, but the fertile darkness from which God might shine forth at any moment, ex nihilo.

In looking at these textual sources, we see the vast importance words and faith have on Pärt. Even when composing instrumental music, Pärt often works from a text: Trisagion (1992) and Orient & Occident (2000) are “set” to Slavonic versions of Orthodox introductory prayers and the Nicene Creed, respectively. The texts, Bouteneff notes, seem to “contain within themselves a latent music.” Paying attention to these texts can draw us closer to a piece’s inherent meaning, shedding light on what the composer intended in creating it. With Pärt there is strong resistance to a kind of post-structuralist framework of artistic communication, where authorial intent is either nonexistent or second to audience experience. While audience experience is indelible, it is impossible not to reckon with the spiritual nexus of Pärt’s creativity.

Recalling the role of midwife, the goal is thus to translate the life of a text into a strictly musical idiom, such that music qua music can reveal the essence of what the composer is trying to communicate. Here we enter paradox, familiar territory in Christianity. The Word is both expressible and inexpressible, cataphatic and apophatic. After the ascent to comprehension, there is yet another and higher peak—in the words of Pseudo-Dionysius, a realm “beyond unknowing,” a positive silence and darkness, charged with the fullness of God. It is here where, should we come in honesty and vulnerability, acknowledging the spiritual sources of the art, we may meet the artist in true communion. It is here where we may be transformed.

In addition to the choir trip through Europe, I was fortunate to experience another such meeting with Pärt’s music at a performance in 2014, where the composer himself was present. It was the first time Pärt had been to New York in thirty years, and an eclectic audience came to Carnegie Hall in droves to see the man and hear his music—from a large number of Eastern Orthodox clergy to Björk and Keanu Reeves to Bouteneff (the night was produced by the Arvo Pärt Project).

It was the first time I had heard Adam’s Lament. I felt the bright sadness, to be sure, but there was a sense of something larger, deeper, more mysterious at work, something I believe everyone in the concert hall participated in—the meeting of the eternal and temporal, the divine and human, joy and suffering, a music “outside time but emphatically incarnated.”