How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Jamstack

Table of Contents

Since I started coding in earnest at the end of 2021, I’ve used this website as a testing ground for many of the tools I’ve encountered on an almost weekly basis. It’s become a living embodiment of my long, exasperating, but genuinely exciting journey into front-end web development.

That’s a longer story that I want to write about in more depth at some point. But a big piece of it is how I came to build the current iteration of this admittedly eclectic site, which is neither a dev blog nor a design/writing showcase nor a reading journal, but something that combines aspects of them all. In this respect it’s a perfect reflection of my current preoccupations. The ultimate goal was and is to create a site in the simplest and most efficient manner possible, where my creativity could be completely unrestrained. (I should note here for clarification that I think of myself wholly as a web designer with front-end skills, and not as a programmer or software engineer.)

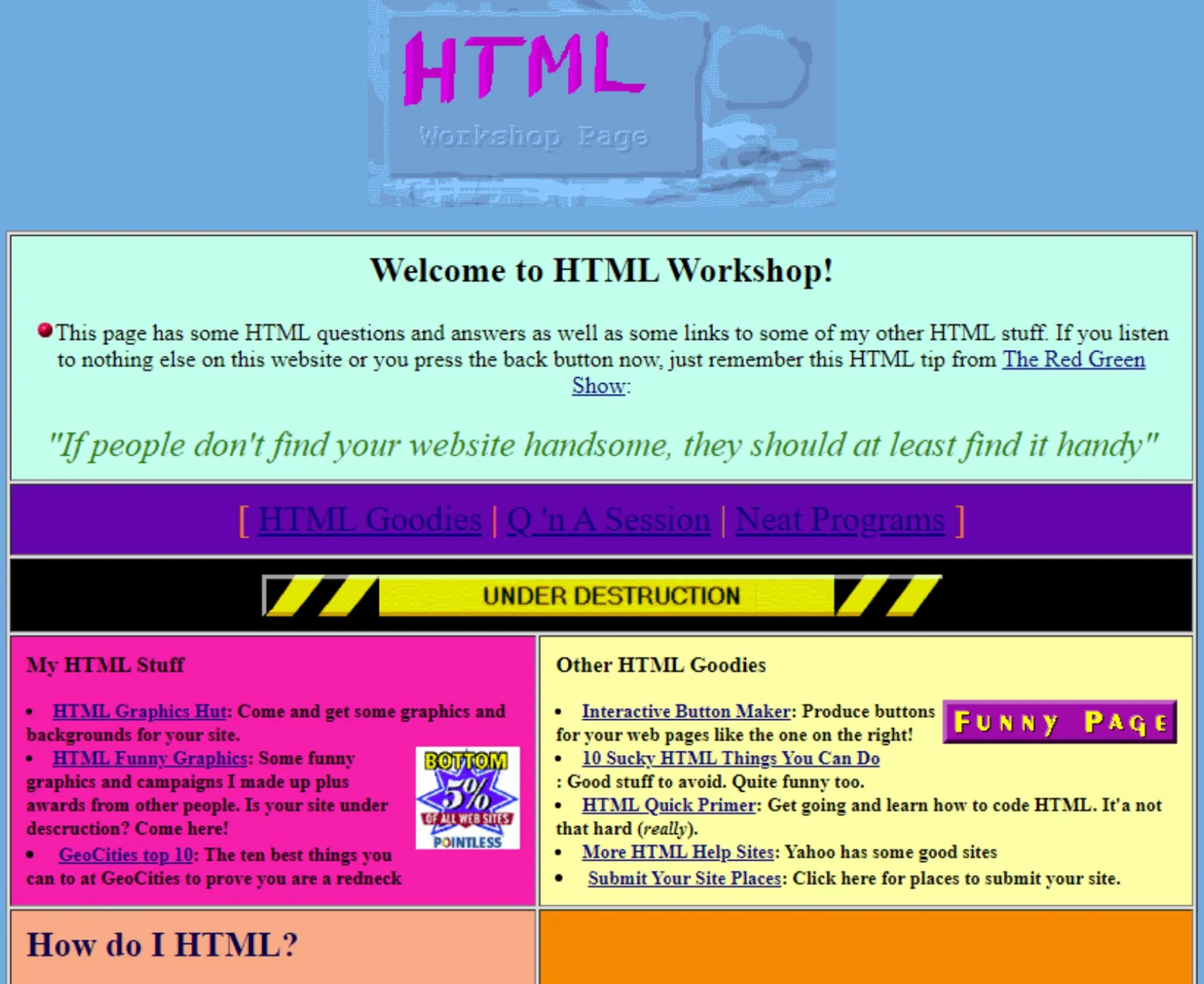

Many of the articles here started their lives as WordPress posts or Google Docs drafts, spent a brief time as entries in a custom CMS app, and are now enjoying their apotheosis as features of a totally custom-built static site using the Jamstack approach—an approach to which I am now completely devoted. In a way, parts of the web are drifting toward the exhilarating and more than slightly anarchic days of when anyone could build a site with HTML, however they wanted, before monolithic approaches dominated (hello, 1996!). In my opinion, this is a good thing and opens up a lot of opportunities for designers. Here’s how it happened for me.

First Attempt: Statamic CMS

Is PHP dead? Definitely not, but I also don’t really want to learn it at this point. There, I said it. And yet PHP was the tool I first reached for when I decided to build this blog from scratch, probably because it was the reigning language when I last tried to master web development about a decade ago.

The good news is that things have improved substantially since the days of WordPress dominance. The PHP ecosystem is bolstered almost single-handedly by the popular Laravel framework, which provides a layer of abstraction that makes the task of building websites and apps much easier than it otherwise would be. I started exploring around the Laravel world and found some promising tools for someone wanting to build a content-based site without too much knowledge of PHP, which eventually led me to Statamic, a Laravel-based content management system (CMS). The less than good news is that I inevitably ran up against some of the same limitations I always encountered with PHP.

But before I get to those complaints, let me sing the praises of Statamic (whose name captures the mix of “static” and “dynamic” that aptly describes a blog-type site). The product is beautiful, the community is extremely helpful, and the overall design sensibility that it represents (a la co-creator Jack McDade) is compelling. As far as I’m concerned, it’s the only PHP-driven WordPress alternative anyone would ever need.

On top of that, Statamic was appealing to me for a few specific reasons. Statamic bills itself as a “flat-file” CMS, meaning your content isn’t stored in a database but is readily available and editable in your code base via Markdown files (more on those in a moment). For most blog or personal sites, a database seems like an overly complex solution to a relatively simple problem—after all, you might only have a few hundred blog posts on a site, and each of those posts have only a few fields (author, date, category, etc.). So the added complexity of integrating with database software (something WordPress does) is unnecessary if your content doesn’t absolutely require it. (To be clear, you can use a database with Statamic, but the default setup is database-less.) This idea of reducing complexity and not over-engineering solutions to simple problems is a recurring theme in what follows.

I like Statamic for a lot of other reasons as well. So why didn’t I use it ultimately for this site? It comes down to a few not insurmountable but significant issues. Without going too deep, it essentially boils down to my old struggle with PHP. More specifically, my struggle to run PHP on a Windows machine. Unhappily, even in the year 2022, a Windows user needs to install and manage a bundle of software just to be able to run a PHP development environment. (As I understand it, the process is much simpler if you’re using macOS—which, I know, seems to provide an answer to my problem. Alas.) I tried classic bundles like WAMP, I tried Laravel tools like Homestead and Sail, I tried custom Docker containers. All were complex, sluggish solutions that felt simply unnecessary for what I wanted to do, which was … to generate HTML and CSS.

Another roadblock was specific to the kind of thing Statamic is—which is a PHP-driven CMS. Although Statamic rightly bills itself as a more superior product than WordPress, at the end of the day they are still both applications that have to run server-side scripting, both to deliver content and to work at all. (Granted, you can employ Statamic as a static site generator (see below), but I did not find this to be a very intuitive process.) In addition to the added complexity in development, this also means you have to deal with the headache of managed hosting. Fine for a network engineer, but mostly a mess for a designer to try to figure out.

Statamic is a great product, and I don’t want to give the impression that all PHP-driven CMS’s are useless or that I would never use them for a project. The point is that the frustrations I had with them as a designer and not programmer drove me to the next stage in my journey, by raising some key questions—if you’re using a database-less, flat-file CMS anyway, why do you need a complex application like Laravel/Statamic to serve your files? Why do you need a bespoke templating system and (cough)outdated(cough) coding language to make this possible? Isn’t there a better, less complex way?

Second Attempt: Eleventy SSG

Enter the Jamstack. Jamstack is an architecture, philosophy, and broad set of tools for building simpler, lighter, and more performance-driven websites. It’s been gaining traction in the last few years and is now having a truly breakout moment. The “JAM” in the stack refers to the independent but interconnected elements of JavaScript, APIs, and Markup, and that just about sums up the broadest extent of its concerns.

The Jamstack approach is about simplifying the way sites are built and the experience developers have while building sites, so that rather than fighting their tools, developers can get on to the business of what (I think) truly matters: to deliver content in the most accessible and efficient HTML and CSS as possible. Compared to what seemed like the overly complex challenges of traditional development, this straightforwardness immediately appealed to me.

Another huge selling point was the freedom to use the best or preferred tool for the job, for each and every job. To me, that’s a huge improvement over monolithic systems of the past, where front-end/back-end processes were tightly coupled. I’m not limited by the abstractions of a particular framework, but can select an approach or tool that makes the most sense to me.

At the core of Jamstack is the idea of serving static sites, which are usually built with the help of a static site generator (SSG). As the “J” in Jamstack indicates, most of these tools are JavaScript based. This required a foray into JavaScript-land, by far a bigger dumpster fire than PHP-land. Nevertheless, it was a foray that I was prepared to make, because like it or not, JavaScript is only going to become more ubiquitous.

Despite the many bewildering, bisyllabic JavaScript frameworks out there that seem to multiply weekly (sample here), the key element for me was the approachability of SSGs. This was especially true for Eleventy (or 11ty), the SSG I eventually used to build this site. Eleventy bills itself as “a simpler static site generator,” which, in the age of React, is a breath of fresh air. Not only does Eleventy ship zero client-side JavaScript with your site, unlike React behemoths such as Next.js—a huge win for simplicity and accessibility in itself—it allows you the freedom to use a variety of templating languages and approaches in building your site that are framework agnostic. This freedom meant that I always felt like what I was doing had a clear link to my intentions, and I was never fighting my tools.

The other game-changing factor for me was Markdown, an extremely flexible and easy-to-use markup language. Markdown has been around for a while, and yes, Statamic and many other CMS solutions use a Markdown content approach as well. But SSGs like Eleventy simplify content authoring for sites like blogs and portfolios. In Eleventy, pages, posts, projects, events, or any other content schema you can imagine live a tangible reality in a Markdown .md file. Every character is subject to manual control. There’s no CMS, database, or any other level of abstraction—your files are just there, ready to be used. (A side note here is that it is possible and relatively straightforward to pull in content from a headless CMS like Sanity or Storyblok and use it in an SSG. You can even combine the approaches!)

Let’s take a look at a few examples. Below is the simplified directory structure for this site. The src directory is where all of the building and content authoring happens, while the _site directory holds the static files that Eleventy builds for deployment on the web. Within src, the _includes sub-directory holds the actual page and component templates (.njk being the filename extension for Nunjucks, my JavaScript templating language of choice).

├── _site/ # The 11ty build directory

├── src/

│ ├── _includes/

│ │ ├── layouts/ # For high-level page layout templates

│ │ │ ├── base.njk

│ │ │ ├── posts-index.njk

│ │ │ ├── post-view.njk

│ │ ├── partials/ # For reusable site components

│ │ │ ├── site-header.njk

│ │ │ ├── site-footer.njk

│ ├── assets/

│ │ ├── images.jpg

│ ├── styles/

│ │ ├── site.css

│ ├── posts/

│ │ ├── essays/

│ │ │ ├── how-i-learned-to-stop-worrying-and-love-the-jamstack.md

│ │ │ ├── another-essay-title.md

│ │ ├── notes/

│ │ │ ├── note-title.md

│ ├── pages/

│ │ ├── index.njk

│ │ ├── posts.njk

│ │ ├── now.njk

├── .eleventy.js # The 11ty config file

├── package.json

├── etc.

What I love about this is that everything is right in front of me—templates, content, styling, etc. Also, the directory structure largely reflects the route structure of the deployed site. In other words, the file src/posts/essays/another-essay-title.md will output to a page that lives at /posts/essays/another-essay-title/ on the live site.

The key element in the .md files is the front matter—in the example below, the stuff in between the fenced --- elements (here written in YAML syntax). The front matter is like a file’s metadata that becomes available to Eleventy for templating/creating content collections, and anything else you can think of. The Markdown file below has front matter items that control the page’s layout template, title, description, and date. The other thing to note is that the tags value tells Eleventy to create a collection of that name—here a collection called posts. Collections are a super powerful feature in Eleventy that let you group content together to do lots of exciting things.

---

layout: "layouts/post-view.njk" # sets rendered page template

title: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Jamstack

description: A short description of the post.

date: 2022-09-21

tags: posts # tells 11ty which collection this belongs to

---

Body of the post in [Markdown](https://www.markdownguide.org/).

Once you have a collection, you can render its data with a templating language—again, I’m using Nunjucks here. On a posts index page template (i.e., a page listing all of our posts), I can loop through the entries and access the collection object’s front matter within its data.

<ul class="post-list">

{% for post in collections.posts %}

<li class="card">

<a href="{{ post.url }}">

<h3>{{ post.data.title }}</h3>

<!-- Date formatted with a custom filter -->

<p>{{ post.data.date | readableDate }}</p>

<p>{{ post.data.description }}</p>

</a>

</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

Then, on another template for the actual post view, I can render the front matter and body directly:

<article>

<h1>{{ title }}</h1>

<p>{{ date | readableDate }}</p>

<!-- Render the Markdown body content as HTML -->

<section>{{ content | safe }}</section>

</article>

Again, what I like about this approach is that everything exists in front of me. Even though SSGs have a learning curve, and they’re all different, making the jump to Jamstack was a challenge that furthered rather than hindered me in my web development journey.

Ultimately, I think these tools do a great job at making web development more accessible by reducing needless complexity. Of course, you can do a lot of the same things with a tool like Statamic, and on top of that, there’s a definite tradeoff between a truly dynamic vs. static site. Jamstack sites wouldn’t be ideal for every project out there, but you’d be surprised at how many use cases it covers. And it’s great having the freedom and independence to do what you want, how you want. When the process is smooth, it means more attention and energy for the fun stuff.

Tech Stack

This site adheres to a pretty basic Jamstack model: a site generator takes content authored in Markdown and builds static web pages, which are then deployed on a serverless cloud platform. Here is the full list of tools I used to build this site:

Command Line – Git Bash

I use the Git Bash profile on the Windows Terminal app. The Git interface and syntax just makes more sense to me than the default Windows alternatives (although I’m getting Linux-pilled and might very well switch to WSL at some point). I use the command line primarily to interact with the Node.js environment via npm to download dependency tools like PostCSS/Tailwind, Eleventy, and html-minifier, and to spin up a local development server (with no extra environment requirements!).

Text Editor – VS Code

My VS Code setup uses the Jet Brains Mono typeface and Monokai Pro (Octagon filter) color scheme, as well as a bunch of extensions for syntax highlighting and linting.

Content Schema & Authoring – Markdown

I author content in Markdown, either directly in VSCode or with the fantastic iA Writer Markdown editor.

Site Generator – Eleventy + Nunjucks

All of the site’s pages are built with the Eleventy static site generator, and my JavaScript templating language of choice is Nunjucks (although, as noted above, Eleventy supports many more). I also use some of Eleventy’s fantastic plugins, including Image (for image optimization and caching), Fetch (for calling external APIs—in my case, top page views from Fathom Analytics for the “Top Views” sidebar), RSS (for generating an RSS/Atom feed), and Syntax Highlighting (for the cool code highlights as seen in this post).

Styling – Tailwind & Custom CSS

Given the hype and controversy surrounding Tailwind CSS, I had to give it a try. (P.S., I like it, for the most part, and I have some reasonable thoughts I’d like to add to the unrestrained discourse soon.) I’m using it here as a PostCSS plugin alongside others allowing me to write CSS in an SCSS-like syntax. The colors are from Tailwind’s pretty excellent color palette, and fonts are served through Adobe Typekit.

Interactivity – Alpine & Custom JS

I’m using minimal JavaScript on the site, mostly through Alpine.js for menus/dropdowns. Like Tailwind, Alpine allows authoring directly in markup, which I find very convenient. For some other interactive features—dark/light mode, random post generator—I’ve written my own vanilla Javacript.

Deployment – GitHub & Netlify

The source code is stored in a repository on GitHub, which is then used to trigger deploys on the Netlify platform. Netlify is a great service which has extensive features, some of which (like Edge Functions) make static sites virtually indistinguishable from a fully-fledged dynamic site.

Analytics – Fathom

Fathom is privacy-focused analytics tracker that also has a great API, which I’m using to pull top page views to display to users on the home and posts pages.