A tour through the Social Novel, Victorian(-ish) literature, and Weimar Autumn.

A tour through the Social Novel, Victorian(-ish) literature, and Weimar Autumn.

My review of The Historical Figure of Jesus by E.P. Sanders.

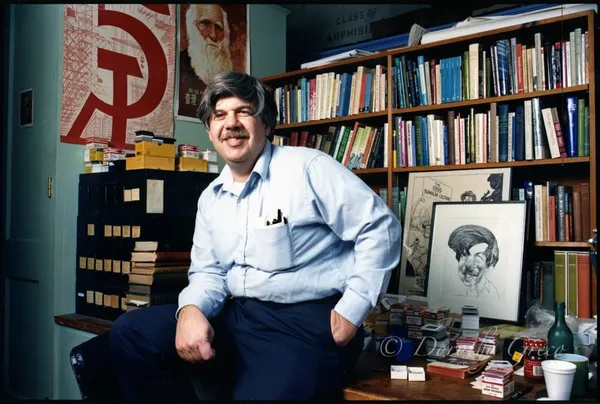

My review of The Non-Jewish Jew and Other Essays by Isaac Deutscher.

This year I devoted almost as much time to building a custom reading tracker app as I did to reading, but I’m still pleased with the quantity and quality of what I read.

The final installment in this post series looks at building a dynamic front-end website for an Airtable reading tracker, using the Deno Fresh server-side rendering framework.

Using Airtable as a back-end to build out a custom reading tracker app.

An effective reading tracker would not only provide a chronological list of titles read, but would uncover the manifold associations of influence and interest that are constantly being formed from the books I read.

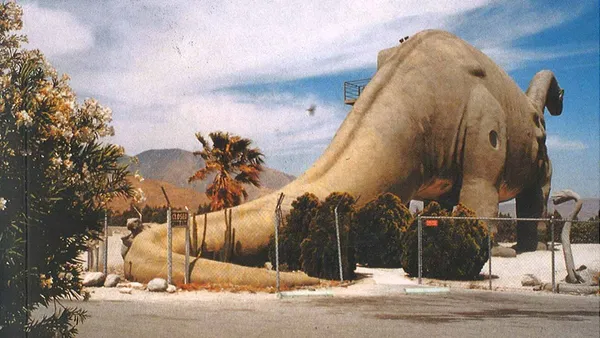

Getting at the heart of what and why postmodernism is remains a challenge that few thinkers have been able to face with as much brilliance and perspicacity as Fredric Jameson, notably in his Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991).

My review of The Weird and the Eerie by Mark Fisher.

My entirely not-of-the-moment, provisional list of favorite reads from 2022, the books that most shaped my thinking this year.

My review of Satantango by László Krasznahorkai.

My review of A World to Win: The Life and Works of Karl Marx by Sven-Eric Liedman.

As tempting as it is to fantasize on what could have been, the historian’s task, Hobsbawm quips, is to analyze what was. And so despite his sympathies and disappointments, Hobsbawm does what no ideological historian can do, but which only the best Marxist thinkers are capable of.

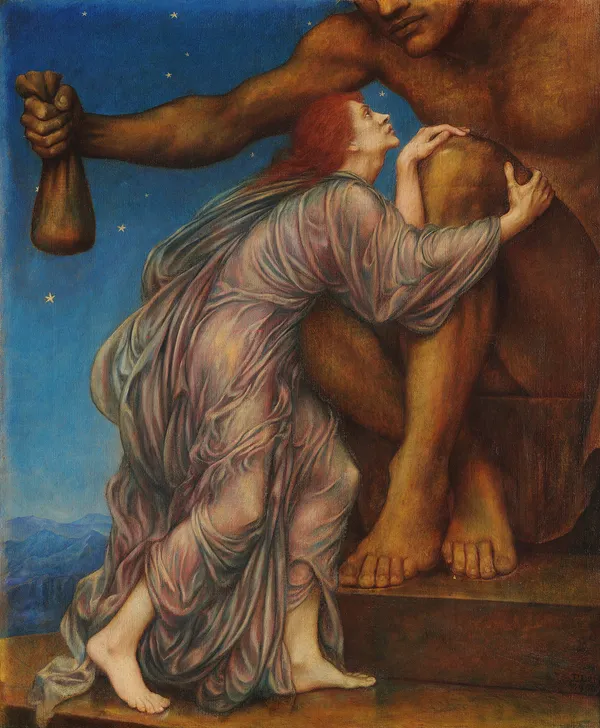

Max Weber famously argued for an “elective affinity” between a Calvinist work ethic and the economic requirements of industrial capitalism. In its insistence on secularized vocation and deferment of worldly pleasure, according to Weber, the Protestant work ethic gave religious sanction to certain kinds of economic activity, namely, the reinvestment of wealth as capital to build society’s productive forces.

The music brings out this sense of inexorableness that the text signals with words like bestimmen (designate, determine, appoint) and the clipped, forceful, almost untranslatable Not (destitution, misery, dire need).

My review of Haymarket’s Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay: The Case for Economic Disobedience and Debt Abolition, for The Bias magazine.

“Cardboard Darwinism,” writes biologist Stephen Jay Gould in an essay of the same name, “is a reductionist, one-way theory about the grafting of information from environment upon organism,” or what amounts to a form of biological determinism.

Nature has a specific history. This is a history in which organic life, inclusive of humanity, acts on and changes the world, at the same time as the world acts on and changes organic life.

Shelving books is, in fact, a dialectical art. Against the rigid, metaphysical hierarchies of the Dewey Decimal System, the dialectical approach begins not with stale Platonic categories (“Philosophy,” “Art,” “Religion”) but with the understanding of the varied internal relations among books.

Walter Rodney’s rejection of rigid models of historical interpretation and “necessary” trajectories of socialist development transcends Cold War limitations. Instead, his authentic use of Marxist historical materialism impels him to begin, per Lenin, with the “concrete analysis of concrete conditions.”

My review of Haymarket’s A People’s Guide to Capitalism: An Introduction to Marxist Economics, for The Bias magazine.

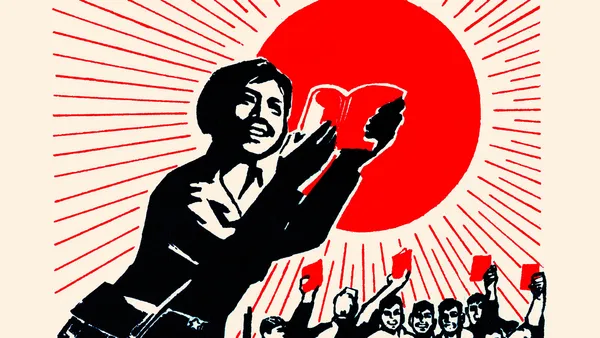

Nothing could be the same in the world after 1917, for “what should never have been became real”—a society where the oppressed masses had overthrown the oppressing classes and where “a total change in the life of the people” was being made.

As a guide to understanding the cultural mythology and socio-geographical history of the singular American city that represents both “the utopia and dystopia for advanced capitalism,” there is none more incisive than Mike Davis’ City of Quartz.

If Marx focused so much on the material, it was because he found it integral to collective human flourishing in a sense similar to the Aristotelian eudamonia—physical, mental, and spiritual well-being achieved through practical activity.

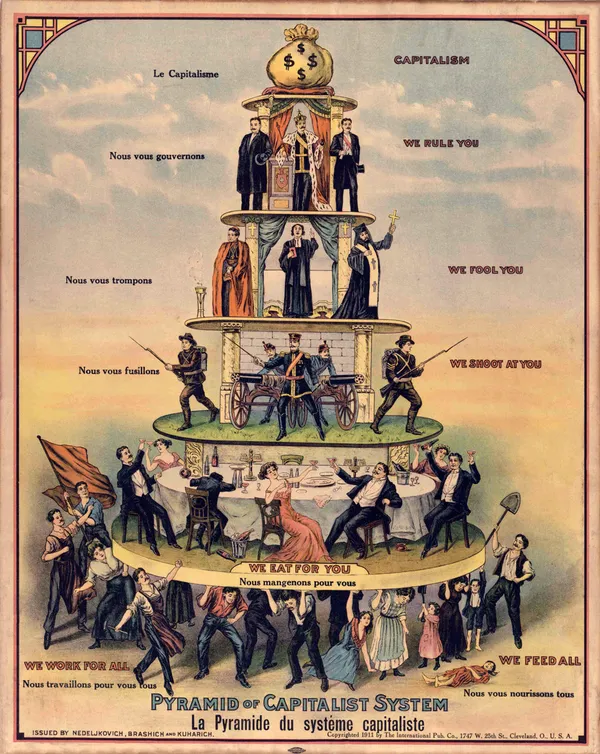

There is a story told about capitalism—mostly by its proponents: classical liberals, American conservatives, libertarians, and the like; but also sometimes inadvertently by its Marxist critics—that sees this system as synonymous with human nature in all times and all places.

Thomas’ “metaphysics,” if indeed it can be called that, is neither an overarching rationalist system nor a purely sense-oriented empiricism. Perhaps it is ultimately closer to the dialectical materialism of Karl Marx—a philosophy engaged with the flux of material, historical change and humanity’s common interaction with itself and nature—than it is to any Enlightenment idealism.

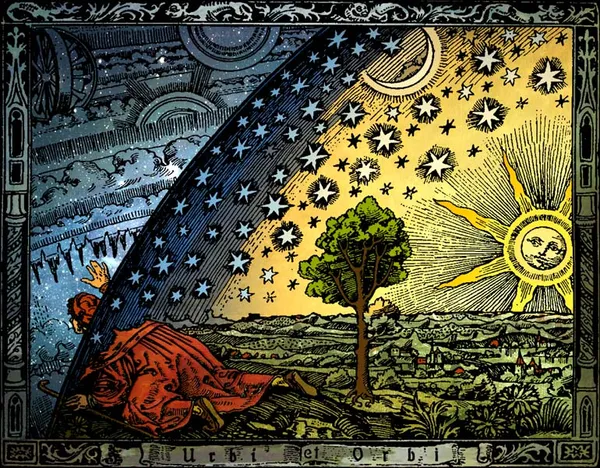

“In the person of Francis the premodern world, so to speak, gathered itself together before coming to an end. For one last time, before the forces of progress thundered off on their triumphant path, one man looked into the motivating thrust behind the whole thing and decisively rejected it: Francis of Assisi, the last Christian.”

Walking is a mode of living that embraces freedom, but this freedom is of a vastly different sort than that offered by the plethora of choices and dependencies that entangle us in the web of our consumerist lives.

It existed once before the nineteenth century, briefly, as part of the vast imperial structure of the Roman Empire. Before that it had been a vague idea from myth—the notion of Italia.

In Rabelais and His World, the Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin argues that Rabelais is the culminating literary expression of the carnival or grotesque idiom of folk humor, an idiom which had developed for over a thousand years (starting with the Roman Saturnalia) as an “unofficial” or subversive culture in the West, complete with its own rites, rules, and symbols.

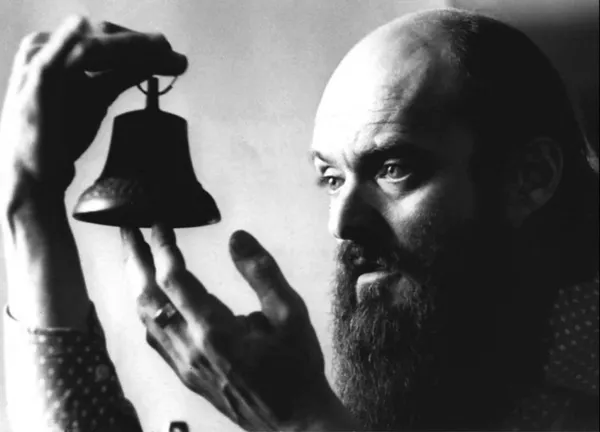

In the introduction to Arvo Pärt: Out of Silence, theologian and musician Peter Bouteneff notes that the tendency to describe first encounters with Pärt grows out of his music’s singular, transformative quality—an evocative spirituality that has captivated believer and non-believer alike.