My review of The Non-Jewish Jew and Other Essays by Isaac Deutscher.

My review of The Non-Jewish Jew and Other Essays by Isaac Deutscher.

Nikos Kazantzakis’ towering literary output reflects a lifelong effort to articulate both spiritual and political radicalisms, for which the figure of Christ is often the embodiment.

My review of A World to Win: The Life and Works of Karl Marx by Sven-Eric Liedman.

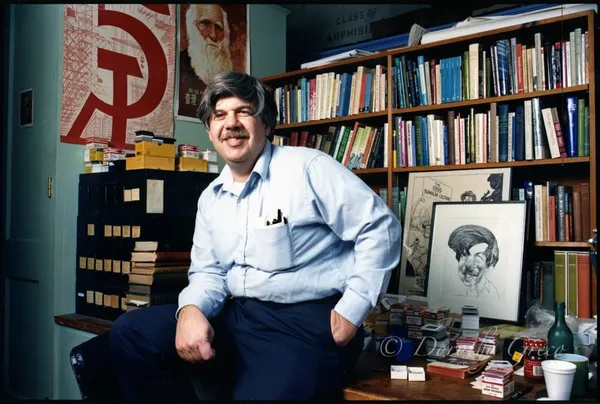

As tempting as it is to fantasize on what could have been, the historian’s task, Hobsbawm quips, is to analyze what was. And so despite his sympathies and disappointments, Hobsbawm does what no ideological historian can do, but which only the best Marxist thinkers are capable of.

My review of Haymarket’s Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay: The Case for Economic Disobedience and Debt Abolition, for The Bias magazine.

“Cardboard Darwinism,” writes biologist Stephen Jay Gould in an essay of the same name, “is a reductionist, one-way theory about the grafting of information from environment upon organism,” or what amounts to a form of biological determinism.

Nature has a specific history. This is a history in which organic life, inclusive of humanity, acts on and changes the world, at the same time as the world acts on and changes organic life.

Walter Rodney’s rejection of rigid models of historical interpretation and “necessary” trajectories of socialist development transcends Cold War limitations. Instead, his authentic use of Marxist historical materialism impels him to begin, per Lenin, with the “concrete analysis of concrete conditions.”

My review of Haymarket’s A People’s Guide to Capitalism: An Introduction to Marxist Economics, for The Bias magazine.

Nothing could be the same in the world after 1917, for “what should never have been became real”—a society where the oppressed masses had overthrown the oppressing classes and where “a total change in the life of the people” was being made.

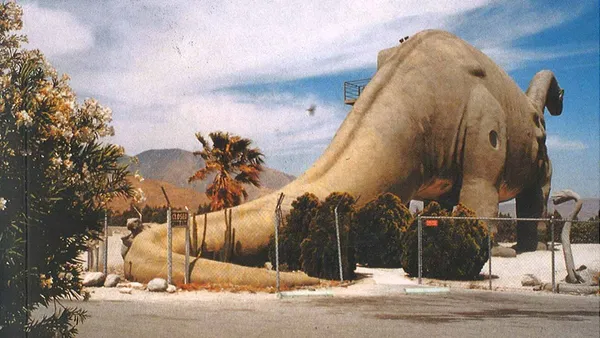

As a guide to understanding the cultural mythology and socio-geographical history of the singular American city that represents both “the utopia and dystopia for advanced capitalism,” there is none more incisive than Mike Davis’ City of Quartz.

If Marx focused so much on the material, it was because he found it integral to collective human flourishing in a sense similar to the Aristotelian eudamonia—physical, mental, and spiritual well-being achieved through practical activity.

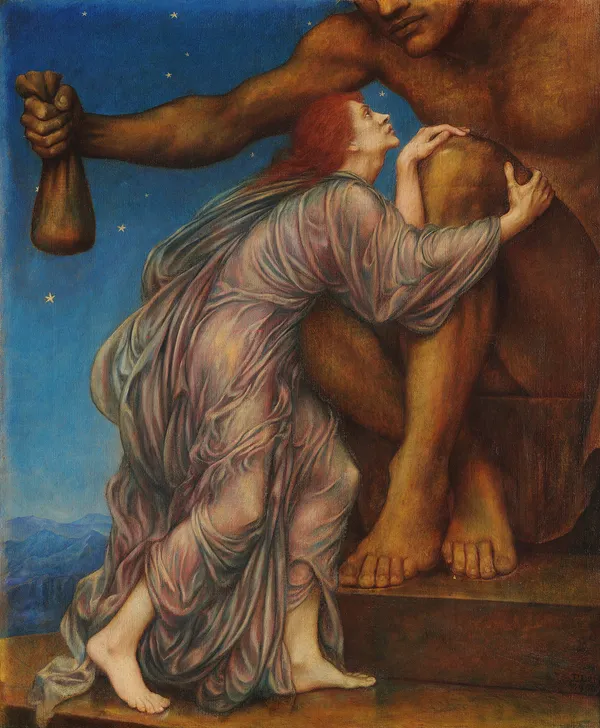

“In the person of Francis the premodern world, so to speak, gathered itself together before coming to an end. For one last time, before the forces of progress thundered off on their triumphant path, one man looked into the motivating thrust behind the whole thing and decisively rejected it: Francis of Assisi, the last Christian.”

It existed once before the nineteenth century, briefly, as part of the vast imperial structure of the Roman Empire. Before that it had been a vague idea from myth—the notion of Italia.